For TimesOnline,

Kitty Kelley writes:

Jennifer Fitzgerald toyed with the long string of pearls around her neck as she waited outside the Oval Office to have her farewell photo taken with President Gerald Ford. Just as the door opened, she broke the strand — but not her stride. She smiled and let the broken pearls dangle as she posed with the president.

It was November 30, 1974. Fitzgerald, personal assistant to one of Ford’s aides, was leaving for the People’s Republic of China to become secretary to the new chief of the American mission there, George Bush.

Bush could hardly wait. His first entry in the new diary he started in Beijing said how much he was looking forward to her arrival.

He had never been a compulsive womaniser. Rather, he maintained a few flirtatious relationships which his wife Barbara had tolerated because he never humiliated her. He chose his involvements very carefully (usually out of town) so as not to threaten his marriage.

Then along came Fitzgerald, who started out as his secretary and became so much more. Short, blonde and pretty, Jennifer Ann Isobel Patteson-Knight Fitzgerald was 42 years old and divorced when Bush first met her in Washington during the tumultuous months of the Watergate scandal. He was chairman of the Republican National Committee; she worked for one of the committee’s officials.

Professionally, Bush’s move from Washington to Beijing would enhance his credentials as he clawed his way to the presidency; but personally it would discombobulate his 30-year-old marriage, prompt his wife to burn her love letters and eventually lead to her severe depression.

“It wasn’t just another woman,” said someone close to the situation, discussing the wedge that came between Bush and Barbara. “It was a woman who came to exert enormous influence over George for many, many years . . . She became in essence his other wife . . . his office wife.”

In those days Beijing was a remote outpost for the staff of the small US mission. Bush told friends when he picked Fitzgerald to join him there that she would be his loyal “buffer” with Henry Kissinger’s State Department.

“I don’t know what particular skills she brought to the job,” recalled one former member of the mission. “She certainly couldn’t type.”

Before her arrival, Barbara Bush suddenly decided to leave Beijing, saying she wanted to spend Thanksgiving and Christmas with her children in America. She did not return for three months.

Fitzgerald landed in Beijing on December 5, 1974, and the next day she and Bush left for a 12-day diplomatic conference in Honolulu.

In his diary, he wrote: “Spent the last two days out of that Sheraton Waikiki madhouse and in the 4999 Kahala apartment — just lovely . . . Checked out the bathhouse again . . . Totally relaxing. Someday I will write a book on massages I have had . . .

“I must confess the Tokyo treatment is the best. Walking the back . . . combination of knees and oil . . . does wonders for the sacroiliac, and a little something for the morale too . . . Flew back to Peking on Iran Airlines. Jennifer and I alone in first class.”

They were not alone for long. Bush’s 73-year-old mother Dorothy had become concerned enough about Barbara’s departure to visit her son over the Christmas holidays.

Bush’s mother was the most important woman in his life. The day before her arrival he wrote: “Mother arrives tomorrow. I have that kind of high school excitement — first vacation feeling.”

“Dotty” Bush understood her son’s driving ambition, and she wanted Barbara to look the part of an important man’s wife. She had urged her white-haired daughter-in-law to try to improve her matronly appearance. Barbara might feel better, she suggested, with a little more exercise.

Long ago, Barbara had athletic skills that impressed the young Bush. They first met in 1941 at a country club Christmas dance in Greenwich, Connecticut. She was 16; he was 17. Neither had dated anyone else before nor even been romantically kissed.

Barbara played soccer and tennis and said she could hold her breath for two laps underwater, all of which validated her with the rampagingly athletic Bush family.

“They were two tomboys, locking each other in closets,” said Bush’s aunt, Mary Carter Walker.

Barbara’s elegant mother, however, would have preferred a more feminine daughter than this big-boned, overweight youngster. Feeling rejected, Barbara ate constantly and developed a caustic tongue.

With Bush she felt pretty for the first time, and he felt adored in turn. As his brother Jonathan said: “She was wild about him. And for George, if anyone wants to be wild about him, it’s fine with him.”

They married in 1944. Over the ensuing decades, as he first made a fortune in Texan oil and then used this to launch his political career, Barbara reinvented herself in the image of his mother.

“George recognised the type of person Barbara was when they first met,” said his friend Fitzhugh Green. “He had seen the same characteristics in his mother: a woman of strong character and personality, direct and honest; one who cares about the outdoors and people, especially children, and is oriented to home life . . . Anyone who has met both mother and wife can see they belong in the same category.”

Marian Javits, the widow of the late Senator Jacob Javits, agreed. “We visited them in China, and while I do not understand Barbara, I do know she adored George,” she said. “I think she saw that her biggest strength was to imitate his mother, almost become his mother . . . Barbara let herself look the way she did on purpose.”

Nadine Eckhardt, who saw a lot of Bush when her husband served in Congress with him, noted his “feminine” side. “George was very ‘femme’. Slim and silly and a hopeless flirt . . . he was cute and we were attracted to each other. It was sort of like when you’re attracted to a gay guy and you know nothing’s going to happen so you just forget about it and be friends.”

Bush and his wife understood and respected each other’s boundaries. Hers was home, where she reigned as the mother of his children; his was work, where he did what he did without threatening his wife’s security or social standing. While his attentions strayed over the years, his family commitment remained solid. He was a mommy’s man, constitutionally incapable of doing anything that would dishonour his mother, and to Dorothy Bush the one abomination that even God could not forgive was divorce.

Bush’s sojourn in Beijing did not last long. Always restless for the next appointment that might put him closer to becoming president, he rarely lasted more than a year in any of his jobs. He wrote to a friend: “I’m sitting out here trying to figure out what to do with my life.”

The answer came in a wire from Henry Kissinger marked “Secret sensitive exclusively eyes only”. It said Ford wanted to nominate him as the new director of the CIA.

“Oh, no, George,” said Barbara. But he said yes. And as a precondition, Bush insisted on bringing Jennifer Fitzgerald with him to the CIA as his confidential assistant. A memo in the Ford Presidential Library, dated November 23, 1975, states: “Please advise me as soon as you have completed office space arrangements for George Bush and Miss Fitzgerald.”

“It’s the most exciting job I’ve had to date,” Bush told friends. He signed personal letters “Head Spook”. Like a little boy, he tested agency disguises by wearing a red wig, false nose, and thick glasses to conduct an official meeting. “He got a big kick out of that,” said Osborne Day, who had been at Yale with him.

Bush was appointed to restore the CIA’s morale and public image after congressional hearings that had exposed its misdeeds — secretly testing drugs on human guinea pigs, spying on American citizens and plotting the assassination of foreign leaders.

Frank Sinatra saw him on television and decided to offer his services to the agency. As the singer was known to be connected to organised crime, the director of the CIA might have thought twice before meeting him; but Bush could hardly wait to meet the mafia’s favourite movie star. He brought Fitzgerald with him. They flew together from Washington to New York on a government plane.

“It was a great evening,” recalled Jonathan Bush, who hosted the meeting. “Sinatra made a very sincere and generous offer to help the CIA in any way possible. He said he was always flying around the world and meeting with people like the Shah of Iran and eating dinner with Prince Philip and socialising with the royal family of Great Britain.”

At the time, Barbara was dealing with a serious depression that more than once led her to the brink of suicide. “George was the only one in the family who knew about it,” Barbara told an interviewer many years later. “He was working such incredible long hours at his job, and I swore to myself I would not burden him.”

She admitted: “I was wallowing in self-pity. I almost wondered why he didn’t leave me. Sometimes the pain was so great, I felt the urge to drive into a tree or into an oncoming car. Then I would pull over to the side of the road until I felt okay.”

Barbara said she did not like his job at the CIA because he could not tell her the agency’s secrets, but in truth she had never played a significant role in his work, except for his political campaigns. Fitzgerald was privy to all that Barbara was not.

Like Beijing, the CIA job did not last. Jimmy Carter, who beat Ford for the presidency in 1976, wanted someone else to head the agency. Bush decided to return to Texas, join the boards of companies controlled by some of his rich friends and lay the foundation for his own presidential campaign. He told Barbara to head for Houston and buy a new house.

Then he looked after his “office wife”. He wrote to Kingman Brewster, the former president of Yale, who was about to become American ambassador to Britain, and obtained a job for Fitzgerald as his special assistant. Conveniently, one of the boards Bush was on had business that took him to London frequently.

“Jennifer only lasted for about a year,” said Brewster’s biographer, Geoffrey Kabaservice. “Kingman was irritated at her frequent absences going to the States to see George . . . Their relationship was no secret to the embassy staff. Everyone knew that she was George’s mistress.”

As his campaign for the presidency picked up speed, Bush set aside several intervals in which he told aides he would not be reachable. He claimed that he was flying to Washington for a secret meeting of former CIA directors. But according to former CIA directors, there were no meetings — secret or otherwise — during that period, and Bush had no assignments of any kind from the CIA.

Although Fitzgerald was a major involvement, she certainly was not the only “other woman” in Bush’s life. During his days at the Republican National Committee, there had been a woman in North Dakota who had divorced her husband and moved to Washington to be closer to Bush. Now, during the 1980 presidential campaign, he had an intense relationship with an attractive young blonde photographer. (After the election, he would offer her a job as his chief photographer, which she would decline because of their romance.)

Fitzgerald was kept out of the campaign at the insistence of James Baker, his old friend and campaign manager, who threatened to resign if he had to deal with “that impossible woman”, as he called her.

“Jennifer was his closest confidante, much to the consternation of many of his closest friends,” recalled the political consultant Ed Rollins. “The only guy able to stare Bush down about Jennifer was Jim Baker.”

Bush’s bid for the Republican presidential nomination failed, but he became Ronald Reagan’s running mate. After their election victory he insisted that Fitzgerald come back as part of his vice-presidential staff.

“I remember when Bush brought his secretaries over to see their new offices,” said Kathleen Lay Ambrose, a vice-presidential aide with the outgoing administration. “We were agog because each one of them was wearing a mink coat. That was such an eye-opener in 1981. Secretaries in mink coats!

“Jennifer Fitzgerald had the best of the minks, and we figured that was because she was . . . well . . . you know . . . Bush’s mistress.” Fitzgerald returned more powerful than ever and soon tangled with Bush’s top political aide, Rich Bond, who became so frustrated that he told the vice-president he would have to leave unless she was reined in.

“Jim Baker made me make that choice once before,” Bush said, “and I made the wrong choice.” Bond had no option but to resign.

Within weeks the new vice-president’s extramarital dalliances flashed up on Nancy Reagan’s radar screen, and she gleefully related every salacious morsel.

When Bush heard the president’s wife was “rumour-mongering”, he wrote in his diary: “I always knew Nancy didn’t like me very much, but there is nothing we can do about all of that. I feel sorry for her, but the main thing is, I feel sorry for President Reagan.”

Nancy lapped up an incident witnessed by some of the Reagans’ closest friends who were having dinner at Le Lion d’Or in Washington on the evening of March 18, 1981.

“Suddenly there was a great commotion as the security men accompanying the secretary of state (Alexander Haig) and the attorney-general (William French Smith) converged on our table,” recalled one of the five dinner guests. “They started jabbering into their walkie-talkies, and then whispered to Haig and Smith, who both jumped up and left the restaurant.

“The two men returned about 45 minutes later, laughing their heads off. They said they had had to bail out George Bush, who’d been in a traffic accident with his girlfriend. Bush had not wanted the incident to appear on the (Washington) DC police blotter, so he had his security men contact Haig and Smith. They took care of things for him, then came back to dinner.”

Michael Kernan, a former editor at The Washington Post, recalls another incident: “Bush was visiting a woman late at night over by the Chinese embassy on Connecticut Avenue and a fire broke out. The DC fire department came, but Bush’s secret service would not let the firemen into the building until they got the vice-president out the back door. We all knew about it at the paper,but nobody wrote about it in those days.”

For most of the Reagan presidency, Fitzgerald had the title of the vice-president’s “executive assistant”. In the spring of 1984 she accompanied him to nuclear disarmament talks in Geneva, where they registered in separate hotel rooms. One night a lawyer from the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency had to deliver some papers to Fitzgerald. The lawyer knocked on Fitzgerald’s door after midnight and was startled when Bush opened it in his pyjamas. After the talks, the vice-president and Fitzgerald shared a cottage, Chateau de Bellerive, on Lake Geneva.

Some aides wondered what Bush saw in Fitzgerald, who was now in her fifties and no longer the pretty divorcée he had first met.

“We all were aware of their relationship — whatever it was,” said an assistant to Craig Fuller, Bush’s chief of staff. “The younger women on staff just couldn’t fathom someone who looked as weirdly out of style as Jennifer sleeping with the vice-president. The men couldn’t figure it either, but there is no denying the connection between them.

“I can’t explain it, other than to say that Jennifer was a doter. She made George feel that he was God’s gift to mankind. She’d bat her eyes and gush all over him. She’d poof her hair, put on lipstick and spray perfume every time she walked into his office in her high stiletto heels.

“Still, she was probably a treat from Bar, who is no gusher. Bar would just as soon say ‘George, cut the crap’ as ‘open the door’. Jennifer was an ego trip for him. She made him feel good about himself.

“She catered to the vain and petty side of George Bush in ways that the rest of us would not have done. For example, he wanted his office on the Hill to be redecorated, and so Jennifer brought him decorator boards with colour schemes and styles and swatches. I remember he wanted blue draperies and threw a tantrum when the draperies weren’t the right shade of blue.

“I was stunned that the vice-president of the United States was focusing on something so small and incidental, but I guess that’s all he really had to do . . . By then he had become so intellectually lazy that he would not spend any time reading the briefs prepared for him. I think he had been a bureaucrat for so long that he simply relied on people to tell him what he needed to know. He did not think for himself. He was verbally inarticulate and could not enunciate a clear concept or formulate ideas.”

Another former member of the vice-president’s staff said: “She was a powerful woman in that she could influence the vice-president more than anyone else, but she was miserable for morale. She was insecure as far as her intellectual capacity because she did not have a college education.”

This source said everyone on his staff sighed with relief when Fitzgerald left the West Wing of the White House for Capitol Hill to become Bush’s chief lobbyist with Congress as he prepared his successful bid for the presidency in 1988.

“One of the reasons she wanted to transfer was to assert she had substantive knowledge and was not just a secretary/scheduler. In effect that’s really all the Veep’s congressional office did, but everyone wanted her out of the office, so they conspired to flatter her into thinking she’d be taken much more seriously if she transferred to the Hill. We all encouraged her in that fantasy and it worked . . . But it did not diminish her influence over the vice-president. It only got her out of our hair.”

“You cannot overestimate her influence on Bush,” said the former assistant to his chief of staff. “He went whenever she called. If she wanted him to meet with a senator or a congressman, we had to change his schedule to do it. Those were his orders.” This source added: “After he became president, Jennifer was shipped off to the State Department so there wouldn’t be any questions regarding their relationship. I also think Barbara did not want her in the White House.

“Whatever, there was a definite decision made that Jennifer would be a target so she had to be moved away from Bush. Jim Baker (the new secretary of state) was the only one who could counterbalance her. So they put her under him.”

Rumours about Fitzgerald started to surface at last in the media. Susan King, a television correspondent, did a story on the campaign whispers about Bush and other women. “He was furious with me,” King said. “I didn’t say in the piece that he and Jennifer were having an affair, and it’s not a story I’d submit for a prize, but it was legitimate to raise the issue because everyone was talking about it at the time. Barbara did not like Jennifer and did not want her around. That was clear to all of us on the campaign.”

In January 1989, after Bush’s presidential election victory, The Washington Post felt bold enough to report slyly: “Jennifer Fitzgerald, who has served president-elect George Bush in a variety of positions . . . is expected to be named deputy chief of protocol in the new administration.”

A year later the Post broke the story that she was fined $648 by the US Customs Service for “misdescribing” the value of a furlined raincoat ($1,100) and failing to declare a silver-fox cape ($1,300) after an official trip to Argentina for the inauguration of President Carlos Menem. Fitzgerald was suspended for two weeks without pay, but she did not lose her presidential appointment.

Barbara, meanwhile, came into her own at last as an extremely popular first lady who made the most of her grandmotherly image.

“I was working at CBS-TV when I first met the Bushes,” recalled Carol Ross Joynt. “He came into the green room with a grey-haired woman who I thought was his mother. Someone told me she was his wife, and I became fascinated by their dynamic because they were not a matched pair . . . He engaged women immediately. He’s not a lecher, but he makes eye contact with sexual energy. He’s polite and does not behave improperly — he’s no Bill Clinton — but the sexual message is there.

“She (Barbara) is oblivious to it all. She’s supremely confident and in charge of him like a mother overseeing her child. It’s clear that she’s the one in the relationship who totally wears the pants . . . it’s also clear that he relies on her.”

Roberta Hornig Draper, whose husband was the US consul-general in Jerusalem, met the Bushes when they visited Israel. “Barbara seemed to wet-nurse George like a little boy. She brushed the dandruff off his shoulders, she straightened his tie, and she was always pushing him along the way. She didn’t tie his shoes or wipe his runny nose, but you get the idea.”

Bush’s relationship with Fitzgerald finally became public during his re-election campaign in 1992, after the sexual peccadillos of the rival candidate, Bill Clinton, had already been well aired.

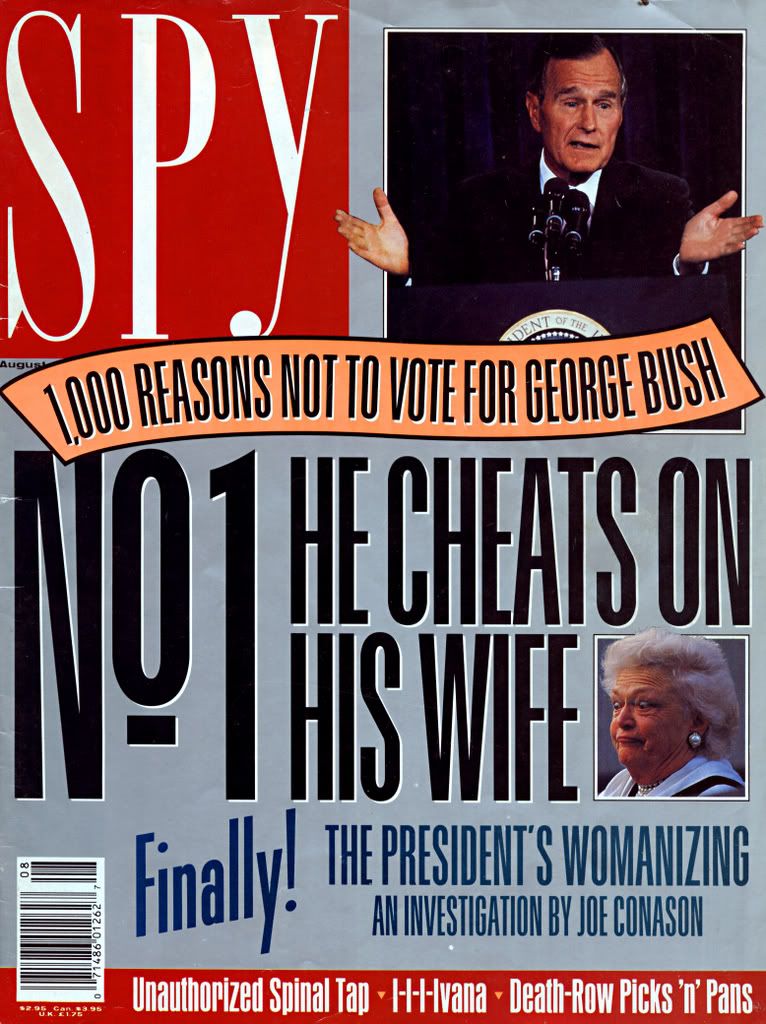

On August 11, the New York Post published a front page story headlined “The Bush affair”, complete with photos of Bush and Fitzgerald, who some people thought bore an eerie resemblance to Barbara.

Usually, the president of the United States does not have his entire family present at a press conference, but the White House made sure that his 91-year-old mother, his wife, his children, their spouses, their pets and all of the grandchildren buttressed Bush when he faced the media that morning.

Thin-lipped with anger, he branded the report a lie. Sensing his fury, one of his granddaughters burst into tears.

Barbara branded it “an outrage”. And Fitzgerald’s 86-year-old mother, Frances Patteson-Knight, whose home in Virginia was adorned with a wide selection of silver-framed photos of Jennifer and George Bush, dismissed it as “ridiculous”.

“Jennifer is completely tortured by this whole business,” she said. She doesn’t know what to do. She thinks it is all just horrible, horrible.”

She added, however, that her daughter — who by then was 60 — had not heard from the president. “She is very disappointed by Bush’s reaction . . . She respects him because he’s president, but doesn’t think he’s acted like a man here. She is very hurt by his lack of support. I don’t think he called her. If he did, she would be less desperate.”

The denials meant nothing to all those who had observed Bush and Fitzgerald together for two decades.

Years later, Carol Taylor Gray, the former wife of the White House counsel C Boyden Gray, said: “Jennifer was a fact of life in George’s life. Period. End of discussion. It was what it was. No one knew that better than my husband, who worked for George Bush for 12 years. We talked about it constantly . . . No one held it against George.

“Actually, I liked Jennifer — she was petite and attractive, and she made him happy, so I’m glad he had her in his life to give him a little joy . . . I know this is heresy to say because Barbara Bush is adored by the country and looks like such a sweet old grandmother, but the country doesn’t know her like I do . . . I don’t think she has a good heart . . . she’s not a nice woman.”