The New York Times reports:

Rising prices for cooking oil are forcing residents of Asia’s largest slum, in Mumbai, India, to ration every drop. Bakeries in the United States are fretting over higher shortening costs. And here in Malaysia, brand-new factories built to convert vegetable oil into diesel sit idle, their owners unable to afford the raw material.

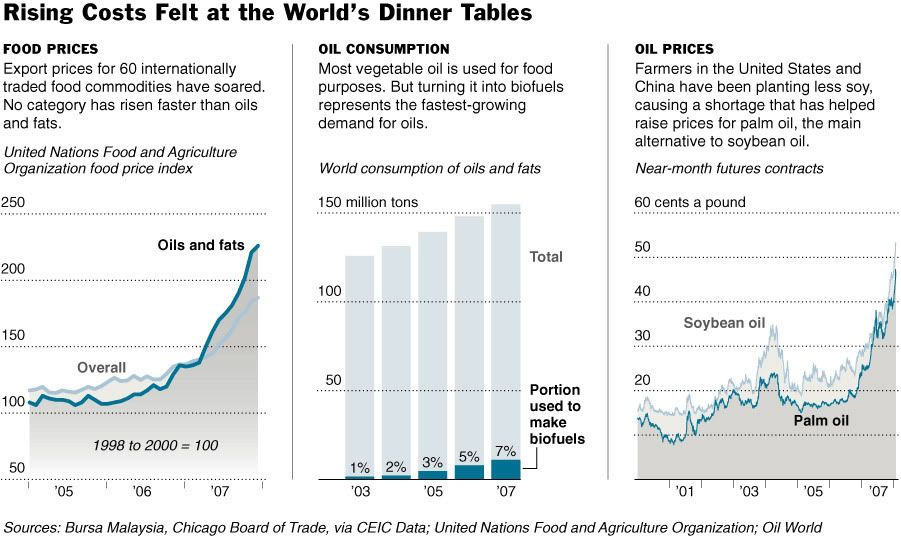

The food price index of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, based on export prices for 60 internationally traded foodstuffs, climbed 37 percent last year. That was on top of a 14 percent increase in 2006, and the trend has accelerated this winter.

In some poor countries, desperation is taking hold. Just in the last week, protests have erupted in Pakistan over wheat shortages, and in Indonesia over soybean shortages. Egypt has banned rice exports to keep food at home, and China has put price controls on cooking oil, grain, meat, milk and eggs.

According to the F.A.O., food riots have erupted in recent months in Guinea, Mauritania, Mexico, Morocco, Senegal, Uzbekistan and Yemen.

“The urban poor, the rural landless and small and marginal farmers stand to lose,” said He Changchui, the agency’s chief representative for Asia and the Pacific.

A startling change is unfolding in the world’s food markets. Soaring fuel prices have altered the equation for growing food and transporting it across the globe. Huge demand for biofuels has created tension between using land to produce fuel and using it for food.

A growing middle class in the developing world is demanding more protein, from pork and hamburgers to chicken and ice cream. And all this is happening even as global climate change may be starting to make it harder to grow food in some of the places best equipped to do so, like Australia.

In the last few years, world demand for crops and meat has been rising sharply. It remains an open question how and when the supply will catch up. For the foreseeable future, that probably means higher prices at the grocery store and fatter paychecks for farmers of major crops like corn, wheat and soybeans.

There may be worse inflation to come. Food experts say steep increases in commodity prices have not fully made their way to street stalls in the developing world or supermarkets in the West.

Governments in many poor countries have tried to respond by stepping up food subsidies, imposing or tightening price controls, restricting exports and cutting food import duties.

These temporary measures are already breaking down. Across Southeast Asia, for example, families have been hoarding palm oil. Smugglers have been bidding up prices as they move the oil from more subsidized markets, like Malaysia’s, to less subsidized markets, like Singapore’s.

No category of food prices has risen as quickly this winter as so-called edible oils — with sometimes tragic results. When a Carrefour store in Chongqing, China, announced a limited-time cooking oil promotion in November, a stampede of would-be buyers left 3 people dead and 31 injured.

Cooking oil may seem a trifling expense in the West. But in the developing world, cooking oil is an important source of calories and represents one of the biggest cash outlays for poor families, which grow much of their own food but have to buy oil in which to cook it.

Few crops illustrate the emerging problems in the global food chain as well as palm oil, a vital commodity in much of the world and particularly Asia. From jungles and street markets in Southeast Asia to food companies in the United States and biodiesel factories in Europe, soaring prices for the oil are drawing environmentalists, energy companies, consumers, indigenous peoples and governments into acrimonious disputes.

The oil palm is a stout-trunked tree with a spray of frilly fronds at the top that make it look like an enormous sea anemone. The trees, with their distinctive, star-like patterns of leaves, cover an eighth of the entire land area of Malaysia and even greater acreage in nearby Indonesia.

An Efficient Producer

The palm is a highly efficient producer of vegetable oil, squeezed from the tree’s thick bunches of plum-size bright red fruit. An acre of oil palms yields as much oil as eight acres of soybeans, the main rival for oil palms; rapeseed, used to make canola oil, is a distant third. Among major crops, only sugar cane comes close to rivaling oil palms in calories of human food per acre.

Palm oil prices have jumped nearly 70 percent in the last year because supply has grown slowly while demand has soared.

Farmers and plantation companies are responding to the higher prices, clearing hundreds of thousands of acres of tropical forest to replant with rows of oil palms. But an oil palm takes eight years to reach full production. A drought last year in Indonesia and flooding in Peninsular Malaysia helped constrain supply. Worldwide palm oil output climbed just 2.7 percent last year, to 42.1 million tons.

At the same time, palm oil demand is growing steeply for a variety of reasons around the globe. They include shifting decisions among farmers about what to plant, rising consumer demand in China and India for edible oils, and Western subsidies for biofuel production.

American farmers have been planting more corn and less soy because demand for corn-based ethanol has pushed up corn prices. American soybean acreage plunged 19 percent last year, producing a drop in soybean oil output and inventories.

Chinese farmers also cut back soybean acreage last year, as urban sprawl covered prime farmland and the Chinese government provided more incentives for grain.

Yet people in China are also consuming more oils. China not only was the world’s biggest palm oil importer last year, holding steady at 5.2 million tons in the first 11 months of the year, but it also doubled its soybean oil imports to 2.9 million tons, forcing buyers elsewhere to switch to palm oil.

Concerns about nutrition used to hurt palm oil sales, but they are now starting to help. The oil was long regarded in the West as unhealthy, but it has become an attractive option to replace the chemically altered fats known as trans fats, which have lately come to be seen as the least healthy of all fats.

New York City banned trans fats in frying at food service establishments last summer and will ban them in bakery goods this summer. Across the country, manufacturers are trying to replace trans fats. American palm oil imports nearly doubled in the first 11 months of last year, rising by 200,000 tons.

“Four years ago, when this whole no-trans issue started, we processed no palm here," said Mark Weyland, a United States product manager for Loders Croklaan, a Dutch company that supplies palm oil. “Now it’s our biggest seller.”

Last year, conversion of palm oil into fuel was a fast-growing source of demand, but in recent weeks, rising prices have thrown that business into turmoil.

Here on Malaysia’s eastern shore, a series of 45-foot-high green and gray storage tanks connect to a labyrinth of yellow and silver pipes. The gleaming new refinery has the capacity to turn 116,000 tons a year of palm oil into 110,000 tons of a fuel called biodiesel, as well as valuable byproducts like glycerin. Mission Biofuels, an Australian company, finished the refinery last month and is working on an even larger factory next door at the base of a jungle hillside.

But prices have spiked so much that the company cannot cover all its costs and has idled the finished refinery while looking for a new strategy, such as asking a biodiesel buyer to pay a price linked to palm oil costs, and someday switching from palm oil to jatropha, a roadside weed.

“We took a view that palm oil prices were already high; we didn’t think they could go even higher, and then they did,” said Nathan Mahalingam, the company’s managing director.

Growth in Biofuels

Biofuels accounted for almost half the increase in worldwide demand for vegetable oils last year, and represented 7 percent of total consumption of the oils, according to Oil World, a forecasting service in Hamburg, Germany.

The growth of biodiesel, which can be mixed with regular diesel, has been controversial, not only because it competes with food uses of oil but also because of environmental concerns. European conservation groups have been warning that tropical forests are being leveled to make way for oil palm plantations, destroying habitat for orangutans and Sumatran rhinoceroses while also releasing greenhouse gases.

The European Union has moved to restrict imports of palm oil grown in unsustainable ways. The measure has incensed the Malaysian palm oil industry, which had plunged into biofuel production in part to satisfy European demand.

Another controversy involves the treatment of indigenous peoples whose lands have been seized by oil plantations. This has been a particular issue on Borneo.

Anne B. Lasimbang, executive director of the Pacos Trust in the Malaysian state of Sabah in northern Borneo, said that while some indigenous people had benefited from selling palm oil that they grow themselves, many had lost ancestral lands with little to show for it, including lands that used to provide habitats for endangered orangutans.

“Finally, some of the pressures internationally have trickled down. Some of the companies are more open to dialogue; they want to talk to communities,” said Ms. Lasimbang, a member of the Dusun indigenous group. “On our side, we are still suspicious.”

Demand Outstrips Supply

As the multiple conflicts and economic pressures associated with palm oil play out in the global economy, the bottom line seems to be that the world wants more of the oil than it can get.

Even in Malaysia, the center of the global palm oil industry for half a century, spot shortages have cropped up. Recently, as wholesale prices soared, cooking oil refiners complained of inadequate subsidies and cut back production of household oil, sold at low, regulated prices.

Street vendors in the capital, Kuala Lumpur, complain that they cannot find enough cooking oil to prepare roti canai, the flatbread that is the national snack. “It’s very difficult; it’s hard to find,” said one vendor who gave only his first name, Palani, after admitting that he was secretly buying cooking oil intended for households instead of paying the much higher price for commercial use.

Many of the hardest-hit victims of rising food prices are in the vast slums that surround cities in poorer Asian nations. The Kawle family in Mumbai’s sprawling Dharavi slum, a household of nine with just one member working as a laborer for $60 a month, is coping with recent price increases for palm oil.

The family has responded by eating fish once a week instead of twice, seldom cooking vegetables and cutting its monthly rice consumption. Next to go will be the weekly smidgen of lamb.

“If the prices go up again,” said Janaron Kawle, the family patriarch, “we’ll cut the mutton to twice a month and use less oil.”"The Struggle for Palm Oil" (photos by Michael Rubenstein for The New York Times) In the developing world, cooking oil is an important source of calories and represents one of the biggest cash outlays for poor households. A steep rise in prices for palm oil has forced many families in Dharavi, a sprawling slum in Mumbai, India, to use less oil or even cut back on food:

Rajkanya Kawle at home with her family. Of the nine who live in the one-room home, only one member works to support the household. Their monthly income is 2,500 rupees per month, or about $60. The rising cost of palm oil has hit the family hard. The family eats fish one a week, instead of twice, and has cut its rice consumption by 20 percent. "We'll cut the mutton to twice a month and use less oil" if the prices continue to rise, said Janaron Kawle (in red), the head of the family.

Rajkanya Kawle at home with her family. Of the nine who live in the one-room home, only one member works to support the household. Their monthly income is 2,500 rupees per month, or about $60. The rising cost of palm oil has hit the family hard. The family eats fish one a week, instead of twice, and has cut its rice consumption by 20 percent. "We'll cut the mutton to twice a month and use less oil" if the prices continue to rise, said Janaron Kawle (in red), the head of the family. Lakhinder, a factory worker in Dharavi, fries channa daal, a bean, to make snacks at the Shiv Parvati Foods. According to the factory owner, prices for the palm oil have gone up in the past week from 800 rupees per 16 liters to 950 rupees.

Lakhinder, a factory worker in Dharavi, fries channa daal, a bean, to make snacks at the Shiv Parvati Foods. According to the factory owner, prices for the palm oil have gone up in the past week from 800 rupees per 16 liters to 950 rupees. Mrs. Shinde and her husband, Sadashiu Shinde, 66. Their son lends his support by giving the couple 50 to 100 rupees per day -- the equivalent of $1.25 to $2.50.

Mrs. Shinde and her husband, Sadashiu Shinde, 66. Their son lends his support by giving the couple 50 to 100 rupees per day -- the equivalent of $1.25 to $2.50. Salubai Sadashiu Shinde, 62, stands on the ladder leading to her two-room home in Dharavi. Rising palm-oil prices have forced her family to forgo one of two meat meals per week.

Salubai Sadashiu Shinde, 62, stands on the ladder leading to her two-room home in Dharavi. Rising palm-oil prices have forced her family to forgo one of two meat meals per week. Kastura Khandare, with her granddaughter Arpita Khandare, in front of her two-room home in Dharavi. Mrs. Khandare, who cooks for her family of 10, uses "five to six liters per month if we want to eat three meals a day," she said. With two family members earning a combined 5,000 rupees per month, they are still able to use as much oil as they have in the past. But if prices continue to rise, she will have no choice but to reduce their palm oil consumption.

Kastura Khandare, with her granddaughter Arpita Khandare, in front of her two-room home in Dharavi. Mrs. Khandare, who cooks for her family of 10, uses "five to six liters per month if we want to eat three meals a day," she said. With two family members earning a combined 5,000 rupees per month, they are still able to use as much oil as they have in the past. But if prices continue to rise, she will have no choice but to reduce their palm oil consumption. Suresh Chan, a shopkeeper at the Om Ganesh General Store in Dharavi, said many of his customers had stopped purchasing enough oil for the week or a month. Instead, they buy it as needed. "When the price went up last week they couldn't pay more," he said. "They use less oil every day."

Suresh Chan, a shopkeeper at the Om Ganesh General Store in Dharavi, said many of his customers had stopped purchasing enough oil for the week or a month. Instead, they buy it as needed. "When the price went up last week they couldn't pay more," he said. "They use less oil every day." A woman named Memunisha takes a break from doing laundry outside her one-room home in Dharavi. Rising palm oil prices have started to become difficult for her family. "It is difficult," she said. "If the price will go up 20 to 25 rupees, there is no choice, we have to pay it ... we will adjust, there is no second choice. Without the oil we cannot cook." If prices continue to rise, she will have to buy fewer vegetables for her family.

A woman named Memunisha takes a break from doing laundry outside her one-room home in Dharavi. Rising palm oil prices have started to become difficult for her family. "It is difficult," she said. "If the price will go up 20 to 25 rupees, there is no choice, we have to pay it ... we will adjust, there is no second choice. Without the oil we cannot cook." If prices continue to rise, she will have to buy fewer vegetables for her family.

Saturday, January 19, 2008

A New, Global Quandary: Costly Fuel Means Costly Calories

In Mumbai, Rajkanya Kawle, 11, held palm oil for her family’s dinner. The 250 milliliters of oil cost 16 rupees, about 41 cents. This is the other oil shock. From India to Indiana, shortages and soaring prices for palm oil, soybean oil and many other types of vegetable oils are the latest, most striking example of a developing global problem: costly food.

Posted by Maeven at 8:07 PM

Labels: climate change, economy, food, global warming, globalization, India, Indiana, photos, video