The Associated Press reports:

Al-Qaida chief Osama bin Laden called on Europeans to stop helping the United States in the war in Afghanistan, according to excerpts of a new audiotape broadcast Thursday on Al-Jazeera television.

Bin Laden said it was unjust for the United States to have invaded Afghanistan for sheltering him after the Sept. 11 terror attacks, saying he was the "only one responsible" for the deadly assaults on New York and Washington.

"The events of Manhattan were retaliation against the American-Israeli alliance's aggression against our people in Palestine and Lebanon, and I am the only one responsible for it. The Afghan people and government knew nothing about it. America knows that," the al-Qaida leader said in the five-minute tape.

The message appeared to be another attempt by bin Laden to influence public opinion in the West. In 2004, he offered Europeans a truce if they stopped attacking Muslims, then later spoke of a truce with the U.S. In both cases, al-Qaida then denounced those areas for not accepting its offer.

The terror leader said Afghans have been caught up in decades of struggle, first "at the hands of the Russians ... and before their wounds had healed and their grief had ended, they were invaded without right by your unjust governments."

He said that two separate injustices were visited upon Afghanistan as the Taliban was toppled in 2001: First, the war was "waged against the Afghans without right", and second coalition troops have not followed the "protocol of warfare," with the result that most bomb victims have been women and children.

"I have personally witnessed incidents like these, and the matter continues on an almost daily basis," he said.

State Department spokesman Sean McCormack dismissed the new tape as typical of bin Laden's tactics and expressed faith in the European allies.

"I think our NATO allies understand quite clearly what is at stake in Afghanistan as well as elsewhere around the world in fighting the war on terror," he told reporters. "It's going to require a sustained commitment over a period of time and we have seen that kind of commitment from our European allies."

FBI analysts were reviewing the tape but were not immediately able to say how long it was or when it might have been recorded nor could they provide other details. Spokesman Richard Kolko said it was being examined "to determine if it is authentic and for any intelligence value."

"As the FBI has said since 9/11, bin Laden was responsible for the attack," Kolko said in a statement. "In this latest tape, he again acknowledged his responsibility. This should help to clarify for all the conspiracy theorists, again _ the 9/11 attack was done by bin Laden and al-Qaida."

This has been the deadliest year in Afghanistan since the U.S.-led invasion in late 2001, with more than 6,100 people killed _ including more than 800 civilians _ in militant attacks and military operations, according to an Associated Press tally of figures from Afghan and Western officials.

In the new tape, bin Laden said European nations joined the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan "because they had no other alternative, only to be a follower."

"The American tide is ebbing, with God's help, and they will go back to their countries," he said, speaking of Europeans.

Bin Laden urged Europeans to pull away from the fight.

"It is better for you to stand against your leaders who are dropping in on the White House, and to work seriously to lift the injustice against the believers," he said, accusing U.S. forces and their allies of intentionally killing women and children in Afghanistan.

Al-Jazeera aired two brief excerpts of the audiotape, titled "Message to the European Peoples," which al-Qaida had announced Mondday that it would release soon.

Bin Laden issued four public statements earlier this year _ on Sept. 7, Sept. 11, Sept. 20 and Oct. 22. The Sept. 7 video was his first in three years and was issued to mark the sixth anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks.

Al-Qaida has dramatically stepped up its messages _ a pace seen as a sign of its increasing technical sophistication and the relative security felt by its leadership. Bin Laden is believed to be hiding along the Afghan-Pakistan frontier.

Bin Laden's message was the 89th this year by Al-Qaida's media wing, Al-Sahab, an average of one every three days, double the rate in 2006, according to IntelCenter, a U.S. counterterrorism group that monitors militant messaging.

Thursday, November 29, 2007

| [+/-] |

Bin Laden: "Europeans Should End U.S. Help" |

| [+/-] |

Bill Clinton's Claim of Opposing Iraq War From Outset Disputed |

The Washington Post reports:

A former senior aide to then-national security adviser Condoleezza Rice disputed Bill Clinton's statement this week that he "opposed Iraq from the beginning," saying that the former president was privately briefed by top White House officials about war planning in 2003 and that he told them he supported the invasion.

Clinton's comments in Iowa on Tuesday went far beyond more nuanced remarks he made about the conflict in 2003. But the disclosure of his presence in briefings by Rice -- and his private expressions of support -- may add to the headaches that the former president has given his wife's campaign in recent weeks.

Hillary Mann Leverett, at the time the White House director of Persian Gulf affairs, said that Rice and Elliott Abrams, then National Security Council senior director for Near East and North African affairs, met with Clinton several times in the months before the March 2003 invasion to answer any questions he might have. She said she was "shocked" and "astonished" by Clinton's remarks this week, made to voters in Iowa, because she has distinct memories of Abrams "coming back from those meetings literally glowing and boasting that 'we have Clinton's support.'"

Leverett, a former career foreign service officer who said she is not involved in any presidential campaign, said the incident affected her because of her own doubts about the wisdom of an attack. "To hear President Clinton was supportive really silenced whatever questions I had," she recalled. Leverett, who worked in the same office as Abrams at the time, said Rice and Abrams "made it a high priority" to get Clinton's support, meeting with him at least twice. Abrams was tasked to answer Clinton's questions and "took the responsibility very seriously," Leverett said. "Elliott was then very focused on making sure that we followed up on Clinton's questions to keep Clinton happy and on board."

One of the specific questions Clinton asked, Leverett recalled hearing, is what the United States would do if Iraq's "military used chemical weapons against our Gulf allies."

She recalled being told that Clinton made it clear to Rice and Abrams that they could count on his public support for the war if it was necessary.

Rice's spokesman, Sean McCormack, said that "she is not going to comment on past conversations with former presidents in either capacity as [national security adviser] or secretary of state." White House spokesman Gordon Johndroe declined to comment on behalf of Abrams.

Leverett added that the White House at the time had little concern about Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton's support for the war and "they discussed inviting her to various White House events as a sort of reward for her support."

Leverett and her husband, Flynt Leverett, also a former top Rice aide, have become critics of the Bush administration since they left the White House, accusing the administration of trying to censor their writing because of their criticism of Iran policy.

In an interview last night, Sen. Clinton said of her husband's comments, "There was nothing new in what he said."

An adviser to the former president said that, while Clinton recalled meeting with Rice before the war, it was strictly an informational session about technical war planning, not the merits of an invasion. Clinton did not, the adviser said, believe he was being solicited for an opinion about whether to invade.

Although Bill Clinton is still viewed as a political asset, particularly in the hotly contested Democratic primaries, he has also repeatedly made remarks that have put him out of step with his wife's message and irritated Clinton campaign aides who have been forced to address them.

After the Democratic debate in Philadelphia last month, the former president insinuated that his wife's Democratic rivals were mounting attacks on her akin to the "Swift boat" campaign Republicans launched against Sen. John F. Kerry (D-Mass.) during the 2004 race -- an explosive charge that prompted some of Hillary Clinton's rivals to lash out more aggressively than ever.

The following week, Clinton strayed off-message again, continuing to reinforce the theme that other candidates were piling on his wife after her strategists had decided to drop the issue. In a speech on Nov. 12, Clinton complained about the "boys" in the campaign "getting tough" on his wife. It was then that Clinton campaign aides began quietly distancing themselves from the former president, saying his comments were not part of their coordinated effort.

Jay Carson, a longtime Clinton spokesman who recently moved to Sen. Clinton's campaign, quickly sought to put the former president's comments on Iraq into context -- arguing that Clinton had always had concerns about attacking Baghdad.

"This administration assured us that Saddam Hussein had [weapons of mass destruction], that the war was over 2,500 casualties ago and that the insurgency was in its last throes," he said. "Their claim that President Clinton privately offered his support for the war should be viewed with the same level of credibility."

And the campaign made clear that Clinton would remain his wife's chief, and best, surrogate.

"President Clinton is a huge asset to the campaign. Everywhere he goes, he draws large, supportive crowds," said Howard Wolfson, a senior Clinton adviser.

Wednesday, November 28, 2007

| [+/-] |

Journalists Believe Conditions in Iraq Have "Gotten Worse" |

Journalists in Iraq - A Survey of Reporters on the Front Lines

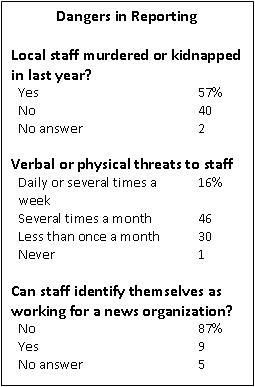

After four years of war in Iraq, the journalists reporting from that country give their coverage a mixed but generally positive assessment, but they believe they have done a better job of covering the American military and the insurgency than they have the lives of ordinary Iraqis. And they do not believe the coverage of Iraq over time has been too negative. If anything, many believe the situation over the course of the war has been worse than the American public has perceived, according to a new survey of journalists covering the war from Iraq.

Above all, the journalists—most of them veteran war correspondents—describe conditions in Iraq as the most perilous they have ever encountered, and this above everything else is influencing the reporting.

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

| [+/-] |

Effort To Turn Sunnis To U.S. Questioned |

Star-Telegram.com reports:

The U.S. campaign to turn Sunni Muslims against Islamic extremists is growing so quickly that Iraq's Shiite Muslim leaders fear that it's out of control and threatens to create a potent armed force that will turn against the government one day.

The U.S., which credits much of the drop in violence to the campaign, is enrolling hundreds of people daily in "concerned local citizens" groups. Nearly 6,000 Sunni Arabs joined a security pact with U.S. forces Wednesday, reportedly the largest single volunteer mobilization since the war began.

About 77,000 Iraqis nationwide, mostly Sunnis, have broken with the insurgents and joined U.S.-backed self-defense groups. As many as 10 groups were created in the past week, bringing the total to 192, according to the U.S.

U.S. officials said they were screening new members, who are generally paid $300 a month to patrol their neighborhoods, and were subjecting them to tough security measures. The officials said they planned to cap membership in the groups at 100,000.

But that hasn't calmed mounting concerns among aides to Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, who charge that some of the groups include terrorists who attack Shiite residents in their neighborhoods. Some of the new "concerned citizens" are occupying houses abandoned by terrified Shiite families, they said.

It also hasn't quieted criticism that the program is trading long-term Iraqi stability for short-term security gains.

"We have tens of thousands of people who are carrying weapons on a contract basis, and when their contracts are finished where will they go?" asked Dr. Safa Hussein, al-Maliki's deputy national security adviser.

At a glance

The latest news in the war in Iraq:

Suicide bombing: Seven U.S. soldiers and five Iraqi civilians were wounded when a female suicide bomber blew herself up near Baqouba, the U.S. military said.

Cholera worries: The U.N. raised new concerns Wednesday about a possible outbreak in Baghdad ahead of the rainy season.

Journalists surveyed: American journalists covering Iraq say they face unprecedented dangers, and many have worked closely with Iraqi colleagues who have been killed or kidnapped, according to a survey by the Project for Excellence in Journalism. Most of the 111 survey participants, veteran war correspondents with experience in Afghanistan, Gaza and Lebanon, called the war in Iraq their most dangerous assignment ever.

| [+/-] |

Bush Welcomes Gore to Oval Office |

The NY Times reports:

Talk about an inconvenient truth. Al Gore finally won his place in the Oval Office on Monday -- right next to George W. Bush. Forever linked by the closest and craziest presidential race in history, the two men were reunited by, of all things, White House tradition.

Gore was among the 2007 Nobel Prize winners who were invited in for a photo and some chatter with the president; Gore got the recognition for his work on global warming.

The two men stood next to other, sharing uncomfortable grins for photographers and reporters, who were quickly ushered in and out.

''Familiar faces,'' the former vice president said of the media. Bush, still smiling, added nothing.

The two also had a 40-minute meeting in the Oval Office, part of Bush's effort to show some outreach to his longtime rival.

Bush aides said it was private and would not comment on it.

Gore, trailed by the press as he left the White House very publicly on foot, allowed that he and Bush spent the whole time talking about global warming.

''He was very gracious in setting up the meeting and it was a very good and substantive conversation,'' Gore said. ''And that's all I want to say about it.''

Gore's presence added unlikely buzz to a photo op that normally would have been buried by Bush's Mideast peace forays. It is not like these two cross paths much. They have not met privately since then-President-elect Bush paid a visit -- short, and not that sweet -- to Gore's residence in December 2000.

That was back when the acrimony was fresh, in a country still in disbelief over an election that seemed never-ending. Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court certified Bush's 537-vote victory margin over Gore in Florida to settle the outcome.

Since then, Gore has not shied away from criticizing Bush; his latest book, ''The Assault on Reason,'' is a relentless attack against the administration. And the White House's response when Gore won the Nobel Prize was less than giddy.

Never mind all that.

''I know that this president does not harbor any resentments,'' White House press secretary Dana Perino said. ''Never has.''

Indeed, the White House tried to make clear that Bush was hosting Gore not out of obligation, but genuine interest.

Bush personally invited Gore. The White House changed its original date to accommodate Gore. And then there was the private Bush-Gore meeting, too.

When it was over, the scene took a bit of turn for the weird.

Gore said he didn't want to comment. But with the media waiting for him, Gore and his wife, Tipper, walked out along Pennsylvania Avenue and up 17th Street, toward his nearby office -- even though the White House is adept at helping people slip away unnoticed if they want.

The media horde followed the Gores for several minutes. When a veteran reporter asked Gore if he missed all the attention, he adeptly turned the question around. ''When you leave this beat,'' he said, ''I'm gonna ask you.''

Monday, November 26, 2007

| [+/-] |

Baath Reconciliation Bill Draws Anger of Shiite Bloc |

A wounded man stands at the scene of a suicide car bomb attack that killed 10 people in Baghdad. (By Hadi Mizban -- Associated Press)

A wounded man stands at the scene of a suicide car bomb attack that killed 10 people in Baghdad. (By Hadi Mizban -- Associated Press)The Washington Post reports:

A draft law that would ease restrictions on former members of Saddam Hussein's Baath Party, a measure seen by the Bush administration as crucial to national reconciliation, was presented in parliament on Sunday for the first time.

A powerful Shiite faction quickly objected to any moves to bring the Baathists back into government jobs, and a table-pounding argument erupted in the closed-door session, forcing postponement of the debate.

Meanwhile Sunday, a suicide attacker using a car bomb killed 10 people and wounded 29 near the Health Ministry building in central Baghdad, Iraqi police said. It was the latest assault to shatter a relative lull in Iraq's violence.

On Friday, a bomb hidden in a box containing birds detonated in the al-Ghazl animal market, killing 15 people and injuring 55, the deadliest attack in the capital in more than two months.

But violence on average is still down, and U.S. commanders and politicians are increasingly concerned that Iraq's government, riven by sect and competing visions, is not taking advantage of the lull to seek political reconciliation. In particular, the measure on Baathists is viewed as key to bridging the rift between Iraq's majority Shiites and minority Sunni Arabs.

In the wake of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion, thousands of members of the Sunni-dominated Baath Party were dismissed from military and government jobs, retaliation for years of persecuting Shiites. The proposed law would allow them to return to certain positions and collect pensions; thousands have already managed to do so unofficially.

Sunday's objections were raised by politicians loyal to Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, who withdrew his supporters from the Shiite-led government of Nouri al-Maliki earlier this year.

The argument was ostensibly triggered by claims that the draft law was improperly presented to the legislative body, without first going to its legal committee. But it was clear that the objections rose from deep-rooted sentiments dating to Iraq's turbulent past.

"We reject the return of Baathists to any executive position, not even a hospital manager," said Shiite lawmaker Liwa Smaysim, the head of Sadr's parliamentary bloc. "Our goal is to prosecute the Baath as a party and regime, not only as a regime."

"The Sadrists see the draft law as permissive with Baathists and it would bring them back their jobs. They think it's an amnesty for them," said Mahmoud Othman, an independent Kurdish lawmaker who attended the session.

"We are against the idea of revenge, we want a real reconciliation. The judiciary decides who committed crimes against Iraqis," he added. "Flexibility and forgiveness are needed to reach this goal."

Aside from the law on Baathists, reconciliation legislation to distribute oil revenue among Iraq's sects, reform the constitution and set a date for provincial elections also remain stalled.

Also Sunday, Iraq's most influential Shiite politician, Abdul Aziz al-Hakim, said the United States needed to back up its claims that Iran is fomenting violence inside Iraq, which Iran has denied. The U.S. military has accused an Iranian-backed Shiite cell in Friday's market bombing.

"These are only accusations raised by the multinational forces, and I think these accusations need more proof," Hakim, leader of the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council, told reporters.

| [+/-] |

Numbers of Iraqi Refugees Returning Home Exaggerated |

Iraqis who had gone to Syria to escape the violence at home arrived in Baghdad on Wednesday.

Iraqis who had gone to Syria to escape the violence at home arrived in Baghdad on Wednesday.

The NY Times reports:

At a row of travel agencies near the highway to Syria, the tide of migration has reversed: the buses and GMC Suburban vans filled with people heading to Damascus run infrequently, while those coming from the border appear every day.

By all accounts, Iraqi families who fled their homes in the past two years are returning to Baghdad.

The description of the scope of the return, however, appears to have been massaged by politics. Returnees have essentially become a currency of progress.

Under intense pressure to show results after months of political stalemate, the government has continued to publicize figures that exaggerate the movement back to Iraq and Iraqis’ confidence that the current lull in violence can be sustained.

On Nov. 7, Brig. Gen. Qassim al-Moussawi, the Iraqi spokesman for the American-Iraqi effort to pacify Baghdad, said that 46,030 people returned to Iraq from abroad in October because of the “improving security situation.”

Last week, Iraq’s minister of displacement and migration, Abdul-Samad Rahman Sultan, announced that 1,600 Iraqis were returning every day, which works out to a similar, or perhaps slightly larger, monthly total.

But in interviews, officials from the ministry acknowledged that the count covered all Iraqis crossing the border, not just returnees. “We didn’t ask them if they were displaced and neither did the Interior Ministry,” said Sattar Nowruz, a spokesman for the Ministry of Displacement and Migration.

As a result, the tally included Iraqi employees of The New York Times who had visited relatives in Syria but were not among the roughly two million Iraqis who have fled the country.

The figures apparently also included three people suspected of being insurgents arrested Saturday near Baquba in Diyala Province. The police described them as local residents who had fled temporarily to Syria, then returned.

Some Iraqi lawmakers said that overly broad figures were being used intentionally.

“They are using this number because they want to show that Maliki is succeeding,” said Salim Abdullah, a lawmaker and member of the largest Sunni bloc, known as the Accordance Front, referring to Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki. “But this does not make the number correct. I think dozens of Iraqis return home daily, but not 1,600.”

A half-dozen owners of Iraqi travel agencies and drivers who regularly travel to Syria agreed that the numbers misrepresented reality.

They said that the flow of returnees peaked last month, with more than 50 families arriving daily from Syria at Baghdad’s main drop-off point. Since Nov. 1, they said, the numbers have declined, and on Sunday morning, during a period when several buses used to appear, only one came.

The travel agents said that they believed that Iraqis would continue to return to Baghdad from Syria and Jordan but that the initial rush appeared to be over.

A United Nations survey released last week, of 110 Iraqi families leaving Syria, also seemed to dispute the contentions of officials in Iraq that people are returning primarily because they feel safer.

The survey found that 46 percent were leaving because they could not afford to stay; 25 percent said they fell victim to a stricter Syrian visa policy; and only 14 percent said they were returning because they had heard about improved security.

Underscoring a widely held sense of hesitation, many of those who come back to Iraq do not return to their homes. Clambering off the bus on Sunday, a woman who gave her name as Um Dima, mother of Dima, said that friends were still warning her not to go back to her house in Dora, a violent neighborhood in south Baghdad. So for now, she said, she will move in with her parents in southern Iraq.

Raad al-Kihani, a prominent Shiite tribal leader in Baghdad and supporter of the prime minister, said that most people returning were still restricted by the fear of sectarian violence. “There are no Shiite families moving back to Sunni neighborhoods and no Sunnis moving back to Shiite neighborhoods,” he said.

The Iraqi government is using incentives and aggressive public relations to try to bring more people home. Iraqi officials plan to pay for buses to transport Iraqis from Syria. Prominent government figures recently visited Saab al-Bor, a largely abandoned town near Baghdad, to emphasize that families should feel safe enough to return.

The Displacement Ministry offers 1 million Iraqi dinar, about $800, to internally displaced families who can prove they have returned home with a letter from the police and their neighborhood council. But the movement has been limited. As of Thursday, 4,358 internally displaced families, about 25,000 people, had returned to their homes in Baghdad, the ministry’s registry of payments to returnees said.

Furthermore, people are still leaving their homes — 28,017 were internally displaced in October, according to the latest United Nations figures. In all, the United Nations estimates that 2.4 million Iraqis are still internally displaced, with many occupying someone else’s home.

Greater numbers will not return to their neighborhoods, some Iraqi lawmakers and independent migration specialists say, until a clear legal framework has been established to help them get their houses back without evicting other displaced families.

“The actions are slow and so many things needs to be done, said Ayaed al-Sammaraie, a member of Parliament and a leader of its largest Sunni Arab bloc. “The main thing people would like is to return to their spots, and it seems there isn’t a plan for that.”

Saturday, November 24, 2007

| [+/-] |

Karl Rove: "How to Beat Hillary" |

"Republicans who think she'll be easy to defeat are wrong. What they should do."

In Newsweek, Karl Rove writes:

I've seen up close the two Clintons America knows. He's a big smile, hand locked on your arm and lots of charms. "Hey, come down and speak at my library. I'd like to talk some politics with you."

And her? She tends to be, well, hard and brittle. I inherited her West Wing office. Shortly after the 2001 Inauguration, I made a little talk saying I appreciated having the office because it had the only full-length vanity mirror in the West Wing, which gave me a chance to improve my rumpled appearance. The senator from New York confronted me shortly after and pointedly said she hadn't put the mirror there. I hadn't said she did, just that the mirror was there. So a few weeks later, in another talk, I repeated the story about the mirror. And shortly thereafter, the junior senator saw me and, again, without a hint of humor or light in her voice, icily said she'd heard I'd repeated the story of the mirror and she … did … not … put … that mirror in the office.

It is a small but telling story: she is tough, persistent and forgets nothing. Those are some of the reasons she is so formidable as a contender, and why Republicans who think she would be easy to beat are wrong. The Republican presidential nomination is the most fluid and unpredictable contest in decades, but the Democratic nominee is likely to be Hillary. Not without a fight, not without losing early contests (probably Iowa, for starters) and not without bruises and bumps.

And so the question to John McCain from a woman at a town hall in South Carolina last Monday was tasteless, but key: "How do we beat the [rhymes with witch]?" Right now, Republicans are focusing much of their fire on Senator Clinton. Criticizing her unites the party, stirs up the unsettled feelings many swing voters have toward her and allows each candidate to say why he is best able to beat her. For now, that's enough. But when a GOP nominee emerges, he needs to remember no Republican is as well known as Hillary. The Republican has room to grow in the polls as voters get a better sense of who he is and what animates him. Here's what he needs to do.

Plan now to introduce yourself again right after winning the nomination. Don't assume everyone knows you. Many will still not know what you've done in real life. Create a narrative that explains your life and commitments. Every presidential election is about change and the future, not the past. So show them who you are in a way that gives the American people hope, optimism and insight. That's the best antidote to the low approval rates of the Republican president. Those numbers will not help the GOP candidate, just as the even lower approval ratings of the Congress will not help the Democratic standard-bearer.

Say in authentic terms what you believe. The GOP nominee must highlight his core convictions to help people understand who he is and to set up a natural contrast with Clinton, both on style and substance. Don't be afraid to say something controversial. The American people want their president to be authentic. And against a Democrat who calculates almost everything, including her accent and laugh, being seen as someone who says what he believes in a direct way will help.

Tackle issues families care about and Republicans too often shy away from. Jobs, the economy, taxes and spending will be big issues this campaign, but some issues that used to be "go to" ones for Republicans, like crime and welfare, don't have as much salience. Concerns like health care, the cost of college and social mobility will be more important. The Republican nominee needs to be confident in talking about these concerns and credible in laying out how he will address them. Be bold in approach and presentation.

Go after people who aren't traditional Republicans. Aggressively campaign for the votes of America's minorities. Go to their communities, listen and learn, demonstrate your engagement and emphasize how your message can provide hope and access to the American Dream for all. The GOP candidate must ask for the vote in every part of the electorate. He needs to do better among minorities, and be seen as trying.

Be strong on Iraq. Democrats have bet on failure. That's looking to be an increasingly bad wager, given the remarkable progress seen recently in Iraq. If the question is who will get out quicker, the answer is Hillary. The Republican candidate wants to recast the question to: who will lead America to victory in a vital battleground in the War on Terror? There will be contentious fights over funding the troops and over intelligence-gathering right after the parties settle on their candidates. Both battles will help the Republican candidate demonstrate who will be stronger in winning the new struggle of the 21st century.

The conventional wisdom now is that Hillary Clinton will be the next president. In reality, she's eminently beatable. Her contentious history evokes unpleasant memories. She lacks her husband's political gifts and rejects much of the centrism he championed. The health-care fiasco showed her style and ideology. All of which helps explain why, for a front runner in an open race for the presidency, she has the highest negatives in history.

While the prospective Republican nominee is talking about her now, the time will come soon when he must spend more time telling his story. By explaining to voters why he deserves to be our next president, he will also make clear why that job should not go to another person named Clinton.

Friday, November 23, 2007

| [+/-] |

U.S. Tipped To Musharraf Emergency Rule |

UPI reports:

Pakistani and U.S. officials say the United States wasn't surprised when President Pervez Musharraf imposed emergency rule in Pakistan, a report says.

Aides and advisers to Musharraf conducted a series of meetings with U.S. diplomats in the capital city of Islamabad just days before the general's Nov. 3 announcement, The Wall Street Journal reported Friday.

A U.S. official familiar with the discussions says they were part of "intensive efforts" to dissuade Musharraf from declaring emergency rule.

"There was never a green light," the U.S. official told The Journal.

However, one of Musharraf's closest advisers says U.S. criticism of the impending move was muted, leading some senior Pakistanis to interpret it as a sign they could proceed.

Friday Pakistan's new Supreme Court declared Musharraf's seizure of emergency powers was legal. It came just one day after the court ruled against another challenge to the general's re-election last month.

| [+/-] |

Democrats' Iraq Plan Could Leave Many Troops In Place For Years |

Democrats' Iraq pullout plan allows for long-term presence

According to Senator Carl Levin of Michigan, discussing an Iraq troop-cut plan last month, US policymakers must consider a multitude of variables when planning reductions. (Alex Wong/Getty Images)

According to Senator Carl Levin of Michigan, discussing an Iraq troop-cut plan last month, US policymakers must consider a multitude of variables when planning reductions. (Alex Wong/Getty Images)The Boston Globe reports:

The Democrats' flagship proposal on Iraq is aimed at bringing most troops home. Yet if enacted, the law would still allow for tens of thousands of US troops to stay deployed for years to come.

This reality - readily acknowledged by Democrats, who say it's still their best shot at curbing the nearly five-year war - has drawn the ire of antiwar groups and bolstered President Bush's prediction that the United States will probably wind up maintaining a hefty long-term presence in Iraq, much as it does in South Korea.

For those who want troops out, "you've got more holes in here than Swiss cheese," said Tom Andrews, national director of the war protest group Win Without War and a former congressman from Maine.

The Democratic proposal would order troops to begin leaving Iraq within 30 days, a requirement Bush is already on track to meet as he begins reversing this year's 30,000 troop buildup. The proposal also sets a goal of ending combat by Dec. 15, 2008.

After that, troops remaining in Iraq would be restricted to three missions: counterterrorism, training Iraqi security forces, and protecting US assets, including diplomats.

This month, Senate Republicans blocked the measure, even though it was tied to $50 billion needed by the military, because they said it would impose an artificial timetable on a war that has been showing signs of progress.

Despite the GOP's fierce opposition and a White House veto threat, military officials and analysts say the proposal leaves open the door for a substantial force to remain behind. Estimates range from as few as 2,000 troops to as many as 70,000 or more to accomplish those three missions.

There are about 164,000 troops in Iraq now.

Major General Michael Barbero, deputy chief of staff for operations in Iraq, declined to estimate how many troops might be needed under the Democrats' plan but said it would be hard to accomplish any of the stated missions without a significant force.

"It's a combination of all of our resources and capabilities to be able to execute these missions the way that we are," Barbero said in a recent phone interview from Baghdad.

For example, Barbero said that "several thousand" troops are assigned to specialized antiterrorism units focused on capturing high-profile terrorist targets. But they often rely on the logistics, security, and intelligence provided by conventional troops, he said.

"When a brigade is operating in a village, meeting with locals, asking questions, collecting human intelligence on these very same [terrorist] organizations, that intelligence comes back and is merged and fed into this counterterrorism unit," Barbero said. "So are they doing counterterrorism operations?

"It's all linked and simultaneous. You can't separate it cleanly like that."

It's also difficult to say precisely how many US troops are tasked with training the Iraqi security forces.

Christine Wormuth, who served as staff director of General James Jones's commission on training Iraqi security forces, said she estimates some 8,000 to 10,000 troops are dedicated to training. These "transition teams" are tasked solely with training and equipping Iraqi police, army, air force, maritime, and intelligence forces.

But an undetermined number of additional troops provide "on the job" training for Iraqi security forces by conducting daily patrols and other combat missions alongside them, she said.

Last year, the Iraq Study Group, a bipartisan commission whose findings were the basis for the Democratic proposal, recommended that 10,000 to 20,000 troops should be embedded with Iraqi combat units.

Senate Democrats who championed the party's proposal say it was written deliberately to give the military flexibility and not cap force levels. Unlike their counterparts in the House, many Senate Democrats have opposed stronger measures that would set firm deadlines on troop withdrawals or effectively force an end to the war by cutting off money for combat.

"There's no way to say down the line how many insurgency threats there will be, how many militia threats there will be, how many Al Qaeda and other terrorist threats there will be," said Senator Carl Levin, Democrat of Michigan, chairman of the Armed Services Committee.

Still, Levin and other Democrats say the United States could still launch effective antiterrorism strikes in Iraq using elite special operations forces without the massive footprint of conventional forces.

"We've been told now that 90 percent of the Iraqi units are capable of taking the lead, so six or nine months from now we would expect those units would not only be taking the lead, they would be handling those missions," he said.

| [+/-] |

Al-Qaida 'Rolodex' Found in Iraq Raid |

UPI reports:

A September raid near the Syrian border uncovered what U.S. military officials term "an al-Qaida Rolodex" of hundreds of foreign fighters in Iraq.

A senior U.S. military official in Baghdad has confirmed to CNN that the raid netted documents listing the identities of more than 700 foreign fighters believed to have entered the country in the past year.

The official said the documents, along with other intelligence, indicated that as many as 60 percent of the foreign fighters were from Saudi Arabia and Libya, CNN reported.

White House spokeswoman Nikki McArthur said the United States continued to work with countries in the region to stem the flow of foreign fighters into Iraq.

"These statistics remind us that extremists continue to go to Iraq because they do not want the United States nor the Iraqis to succeed in establishing a democracy there that is an ally in the way on terror," McArthur told CNN.

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

| [+/-] |

Israel Defying Sanctions Against Iran |

U.S. officials demanding halt to indirect Israel imports of Iranian pistachio nuts

The International Herald Tribune reports:

It's not just Iran's nuclear program that's causing problems for Israel and the U.S. — it's also Iran's pistachio nuts.

The reddish nuts are landing in Israeli shops after funneling through Turkey, violating Israeli law that bans all Iranian imports and angering American officials who are urging Israel to crack down as part of their attempt to keep Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons.

U.S. Undersecretary of Agriculture Mark Keenum said in a meeting with Israeli officials in Rome on Monday that the pistachio imports must stop, a U.S. official confirmed Wednesday. Both the U.S. and Israel have been pushing for new U.N. sanctions to persuade Iran to abandon its nuclear program. Iran insists its ambitions are peaceful.

"This causes great anger, especially since pistachios succeed in coming in through a third country," Israeli Agriculture Minister Shalom Simchon told Israeli Radio. "This has to do with the sanctions but also with the competition between American farmers and Iranian farmers, and we are trying to deal with this."

Simchon said a recent meeting with a senior U.S. agriculture official focused on using technology to detect the origin of pistachios. He said that would involve chemical testing to determine the climate and soil of where the nuts were grown.

In the mid 1990s U.S. officials pressured Israel to block the import of Iranian nuts coming through E.U. member states and winding up in Israel.

The United States has had few diplomatic and economic ties with Iran since a group of Iranian students besieged the American embassy in Tehran in 1979, holding diplomats hostage for 444 days.

Tensions since Iran started pursuing nuclear technology have only heightened, with the U.S. pushing the U.N. to enact new economic sanctions against the country until it gives up the program.

California is the second largest producer of pistachios in the world, according to the former California Pistachio Coalition. Iran is first.

"As a proud native of the golden state (California), I think Israelis should eat American pistachios, not Iranian ones," said Stewart Tuttle, spokesman for the U.S. Embassy in Tel Aviv.

| [+/-] |

Corker "Underwhelmed" with President Bush |

Local news in Chattanooga reports:

Tennessee Senator Bob Corker raised some eyebrows at a luncheon at the Chattanoogan hotel Tuesday with remarks about President Bush.

Speaking to a crowd of about 500 supporters, led by Hamilton County Mayor Claude Ramsey, Corker spoke about a range of issues, including energy, healthcare, and his experiences during his first year as a Senator.

But his remarks about his experiences with the White House during meetings on the war in Iraq left some in the crowd befuddled.

"I was in the White House a number of times to talk about the issue, and I may rankle some in the room saying this, but I was very underwhelmed with what discussions took place at the White House," Corker said.

A few minutes later during a question and answer session a man in the audience asked him to clarify his statement.

"I was concerned about your statement that you were underwhelmed with what was going on in the White House. Did you mean with him or with his staff?"

In response, Corker said, "Let me say this. George Bush is a very compassionate person. He's a very good person. And a lot of people don't see that in him, and there's many people in this room who might disagree with that.... I just felt a little bit underwhelmed by our discussions, the complexity of them, the depth of them. And yet in spite of that, I do believe that the most recent course of action we've pursued is a good one. I feel like what we've lack in our country is a coherent effort that really links together the Treasury Department, all the various departments of our government in a way that really focuses not just on the hard military side of things, but also the soft effort that it takes to build good will among people. I really think much of that has righted itself, I'm just telling you that at that moment in time I felt very underwhelmed, and I'm just being honest. I've said that to them, and to him, and to others. I kind of in a way wish I hadn't said it today." The last comment was greeted with laughter in the crowd.

Corker is a member of the Foreign Relations Committee. He told the audience that before the end of the year he plans to travel to Pakistan, Afghanistan and India to meet with leaders of those countries.

Tuesday, November 20, 2007

| [+/-] |

Raising Children Behind Bars |

The NY Times reports:

The Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974 created a far-sighted partnership between the federal government and the states that agreed to remake often barbaric juvenile justice systems in exchange for federal aid. Unfortunately, those gains have been steadily rolled back since the 1990s when states began sending ever larger numbers of juveniles to adult jails — where they face a high risk of being battered, raped or pushed to suicide. The act is due to be reauthorized this year, and Congress needs to use that opportunity to reverse this destructive trend.

As incredible as it seems, many states regard a child as young as 10 as competent to stand trial in juvenile court. More than 40 states regard children as young as 14 as “of age” and old enough to stand trial in adult court. The scope of the problem is laid out in a new report entitled Jailing Juveniles from the Campaign for Youth Justice, an advocacy group based in Washington. Statistics are notoriously hard to get, but perhaps as many as 150,000 young people under the age of 18 are incarcerated in adult jails in any given year.

As many as half of the young people who are transferred to the adult system are never convicted as adults. Many are never convicted at all. By the time the process has run its course, however, one in five of these young people will have spent more than six months in adult jails.

Some jails try to protect young inmates by placing them in isolation, where they are locked in small cells for 23 hours a day. This worsens mental disorders. The study says that young people are 36 times more likely to commit suicide in an adult jail than in a juvenile facility. Young people who survive adult jail too often return home as damaged and dangerous people. Studies show that they are far more likely to commit violent crimes — and to end up back inside — than those who are handled through the juvenile courts.

The rush to criminalize children has set the country on a dangerous path. Congress must now reshape the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act so that it provides the states with the money and the expertise they need to develop more enlightened juvenile justice policies. For starters, it should rewrite the law to prohibit the confinement of children in adult jails.

Monday, November 19, 2007

| [+/-] |

Daniel Ellsberg Says Sibel Edmonds Case 'Far More Explosive Than Pentagon Papers' |

'Gagged' FBI Whistleblower, Risking Jail, Says American Media Has Refused Her Offer to Disclose Classified Information, Including Criminal Allegations, Information Concerning 'Security of Americans'

Charges Several Mainstream Publications Have Been Informed of 'Full Story' by Other FBI Leakers Nearly a Year Ago, Have Remained Mum...

"I'd say what she has is far more explosive than the Pentagon Papers," Daniel Ellsberg told us in regard to former FBI translator turned whistleblower Sibel Edmonds.The BRAD BLOG reports:

"From what I understand, from what she has to tell, it has a major difference from the Pentagon Papers in that it deals directly with criminal activity and may involve impeachable offenses," Ellsberg explained. "And I don't necessarily mean the President or the Vice-President, though I wouldn't be surprised if the information reached up that high. But other members of the Executive Branch may be impeached as well. And she says similar about Congress."

The BRAD BLOG spoke recently with the legendary 1970's-era whistleblower in the wake of our recent exclusive, detailing Edmonds' announcement that she was prepared to risk prosecution to expose the entirety of the still-classified information that the Bush Administration has "gagged" her from revealing for the past five years under claims of the arcane "State Secrets Privilege".

Ellsberg, the former defense analyst and one-time State Department official, knows well the plight of whistleblowers. He himself was prepared to spend his life in prison for the exposure of some 7,000 pages of classified Department of Defense documents, concerning Executive Branch manipulation of facts and outright lies leading the country into an extended war in Vietnam.

Ellsberg seemed hardly surprised that today's American mainstream broadcast media has so far failed to take Edmonds up on her offer, despite the blockbuster nature of her allegations.

As Edmonds has also alluded, Ellsberg pointed to the New York Times, who "sat on the NSA spying story for over a year" when they "could have put it out before the 2004 election, which might have changed the outcome."

"There will be phone calls going out to the media saying 'don't even think of touching it, you will be prosecuted for violating national security,'" he told us.

"I have been receiving calls from the mainstream media all day," Edmonds recounted the day after we ran the story announcing that she was prepared to violate her gag-order to disclose all of the national security-related criminal allegations she has been kept from disclosing for the past five years.

"The media called from Japan and France and Belgium and Germany and Canada and from all over the world," she told The BRAD BLOG.

"But not from here?," we asked incredulously.

"I'm getting contact from all over the world, but not from here. Isn't that disgusting?," she shot back.

An Iranian-born American citizen, the linguistics expert Edmonds has been described by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) as "the most gagged person in the history of the United States of America" since filing her original complaints at the FBI, where she had been hired in late 2001 to translate a backlog of pre-9/11 wiretaps.

She has previously indicated a litany of criminal corruption, malfeasance, and cover-ups concerning the penetration of the FBI and Departments of State and Defense by foreign agents in senior positions; influence-peddling and bribery by shadowy Turkish interests throughout the U.S. government over several administrations; undisclosed information related to 9/11; including alleged illegal activities of former Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert, and, most recently, two other "well-known" members of Congress who she will now name to the mainstream media.

Edmonds has taken her whistleblower case all the way to the Supreme Court. She, and her allegations, have been confirmed as both serious and extremely credible by the FBI Inspector General, several sitting Senators, both Republican and Democratic, several senior FBI agents, the 9/11 Commission, and dozens of national security and whistleblower advocacy groups. She was even offered the possibility of public hearings on these matters by the Chairman of the U.S. House Government Accountability and Oversight Committee, after briefing his staff in a special high-security area of the U.S. Capitol reserved for the exchange of classified information.

Her extraordinary story was first aired by CBS' 60 Minutes in 2002 (and re-run twice thereafter), and via a detailed 2005 exposé in Vanity Fair.

All while she was unable to violate the yoke of the unprecedented use of the arcane "States Secrets Privilege", invoked by the DoJ in such a draconian fashion that she is still "gagged" from disclosing even innocuous personal details such as her date of birth.

After five years of being vetted and investigated, with a great deal of her allegations having leaked out via others sources and confirmed by myriad sources, her publicly undisclosed claims would appear to be as credible --- and as critically serious to national security --- as any whistleblower in the history of the nation.

After bringing her charges to the FBI, Congress and the nation's highest court --- all of whom failed to take action or legitimately pursue her claims --- she now feels "obligated" to share the information with the American public. But the American Mainstream Media are apparently unwilling to air it.

Three weeks ago, she told The BRAD BLOG she had "exhausted every channel" and was prepared to "let them see how far they're going to get [by bringing] criminal charges against someone who divulges criminal activity." She was ready to disclose all.

Her "promise to the American public" at the time: "If anyone of the major networks --- ABC, NBC, CBS, CNN, MSNBC, FOX --- promise to air the entire segment, without editing, I promise to tell them everything that I know."

"I don't think any of the mainstream media are going to have the guts to do it," she told us. We didn't believe that could be the case. Surely, we thought, loads of folks in the mainstream broadcast media would jump at the chance for such an explosive exclusive. 60 Minutes, after all, had re-run their initial story on her, including interviews with her, Senators Grassley and Leahy, and several FBI agents, not once, but twice!

It turns out, however, that she was correct. So far.

"How Do We Deal With Sibel?"

"I am confident that there is conversation inside the Government as to 'How do we deal with Sibel?'" contends Ellsberg. "The first line of defense is to ensure that she doesn't get into the media. I think any outlet that thought of using her materials would go to to the government and they would be told 'don't touch this, it's communications intelligence.'"

Edmonds, who founded the National Security Whistleblowers Coalition (NSWBC), contends that she's very sensitive to matters of national security and would never reveal information that could put the country at risk.

"I am not about to expose any methods of intelligence gathering. I am not going to expose any ongoing investigations, or even any investigations that may be ongoing," she told us, explaining that all relevant investigations about which she has information were long ago shut down by the government.

"I am not going to name any informant's name. I am not going to jeopardize any ongoing intelligence. Anything I'm going to be talking about, I know they are investigations that have been shut down by January and February of 2002."

"I am Obligated"

When it comes to the sort of Executive Branch classification of information that's been used to stop Edmonds from revealing alleged criminal culpability, she contends it is the government, not she, who is violating the law.

Legally and constitutionally, she asserts, such classification "may not be used to cover up illegal criminal activities with consequences to public health, security, safety and welfare. It cannot be used to cover up illegal activities."

"The reason I went to Congress, the reason I went to the IG, all of this, is that I was obligated to do so. Because they are covering up illegal activities that effect the public health, security and welfare."

"I am obligated," she repeated again.

Ellsberg agrees. "What is involved in protecting Executive Branch crimes, the duty is to protect the law and to uphold and defend the Constitution. Though most don't understand that and they see loyalty to their boss and their party and their secrecy agreement as more important."

"They'll never get in trouble for that," he emphasized. "But they'll get in a lot of trouble if they are truthful to their oath to defend the Constitution."

Whether Edmonds will ever get that opportunity remains unclear.

Why Not YouTube It?

"When you have a publication like Vanity Fair, running a piece and naming someone like Dennis Hastert [as being allegedly involved in bribery by shadowy Turkish interests involved in narcotics trafficking] and nothing happens with it, you think they are going to pay attention to YouTube?" Edmonds explained when we asked why she didn't release the information herself as a video on the Internet.

Readers around the web have asked the same question in the wake of our previous story, which climbed to the top ranks of most linked and recommended at a number of Internet sites such as Digg.com, Reddit.com, DailyKos and others.

"Listen, I'm willing to have these people come after me with a prosecution --- they [the media] should be willing to do their part."

"This is the biggest risk that a citizen has ever taken...I guess, after Ellsberg...And I know why he did that with the New York Times," she explained referring to his giving thousands of pages of documents to the paper, who, at the time, went all the way to the Supreme Court to fight for their right to publish them, as they eventually did.

"What about the BBC? Would you do that?," we asked.

"Why am I going on BBC? This is about this country! This is about this country, and more of America needs to know the true face of the mainstream media," she exclaimed.

"The only way they got away with it was because of the mainstream media. They are the biggest culprit for the state of our country. Whether it's Iraq, or torture or the NSA wiretapping --- which the New York Times sat on for over a year! --- these people are the real culprit."

"Nibbles"

There were some "nibbles," as she called them. A producer from CBS Evening News had contacted The BRAD BLOG within hours of publishing our previous story, asking for Edmonds' contact information to forward to 60 Minutes producers. Nothing has come of it so far.

ABC News also inquired. Despite allowing Presidents and other officials to make previously undisclosed claims on live programs such as This Week and others, they declined to extend the same opportunity to Edmonds. That, despite dozens of high-ranking officials, elected and otherwise, who have heard her claims over the years and repeatedly declared them to be exceedingly credible and meriting serious investigation.

What about Keith Olbermann? Surely he'd pick up this story! A producer at MSNBC's Countdown --- perhaps the outlet most often suggested to us as likely willing to interview her --- expressed interest during multiple inquiries we'd made to them. Each time, the promise was made to call us back with on the record information on whether they would do the interview, and if not, why not. They never called us back.

Edmonds' phone was "ringing off the hook" for requests for interviews from independent radio shows. Ours was too, and our email inbox yielded dozens of similar requests.

But Edmonds has been clear: "I'm gonna do one major interview" to tell all of the 'states secret' information. "Afterwards, I'll do the others. But this is gonna be one round, give it all and say 'here it is.'"

The ground rules seem fair enough. She is risking being rushed off to prison after all.

"Setting Records for Shamelessness"

The mainstream media is "shameless", Ellsberg says, so is Congress, so is Bush.

"He's setting records for shamelessness. He should probably be in the Guinness Book of Records. He doesn't care what he says. And the media is shameless as well, as they'll run anything he says. And Congress is pretty shameless as well. You can't really shame these people."

Without mainstream corporate media attention, Ellsberg contends, Edmonds' story will stay off the radar, and her damaging contentions will do no harm to the powers that be.

"She's not going to shame the media, unless the public are aware that there is a conflict going on. And only the blog-reading public is aware of that. It's a fairly large audience, but it's a small segment of the populace at large."

Unless her claims reach the mainstream, he says, "they don't suffer any risk of being shamed. As long as they hold a united front on this, they don't run the risk of being shamed."

They Already Know

Edmonds revealed an additional tasty morsel while wrapping up one of our recent conversations. One that might help explain the American media's reluctance to jump at the chance for a scoop: apparently many of them already know the story.

"I will name the name of major publications who know the story, and have been sitting on it --- almost a year and a half."

"How do you know they have the story?," we asked.

"I know they have it because people from the FBI have come in and given it to them. They've given them the documents and specific case-numbers on my case."

"These are agents that have said to me, 'if you can get Congress to subpoena me I'll come in and tell it under oath.'"

Yet, despite promises she says she had received from staffers in Rep. Henry Waxman's (D-CA) office to hold hearings once he became chairman of the House Oversight Committee, they no longer respond to her. "The only reason they couldn't hold hearings [previously]," they'd told her, "was because the Republicans were blocking it."

They're not blocking it anymore. Ever since the Democrats have taken control of the House. Nonetheless, there are still no plans for hearings. Even with more than 30,000 people having signed her petition, calling on Waxman to do so.

A spokesperson from his office finally replied to our repeated requests for comment on why they had not yet held hearings on Edmonds' case.

We were told only that there are no hearings currently scheduled on her case. Repeated attempts to gather a more specific explanation or confirmation that the office had previously promised hearings yielded the same answer, and nothing more. No hearing is presently scheduled on the matter.

"It's disgusting," Edmonds said about the broken promises. "They won't do it anymore. It's disgusting."

"This is criminal activity. That's why I went to Congress, to the Courts, to the [FBI] IG. I am obligated to do so. And that's what I've been doing since 2002."

"By not doing so, someone should charge me for not coming forward to say something about this," she continued.

"If they come after me...when they come after me --- to indict me, to bring charges --- it's going to be up to the American public to see it's not about some bogeyman in some Afghanistan cave. It's about an American citizen coming forward to expose information that concerns the security of Americans."

"An American citizen is coming forward to say that, no, they are depriving you of your security."

Ellsberg says there's a reason that the Government, and both political parties, would rather not deal with something as explosive as Sibel's charges. Much like his own case, when the Republican Nixon administration fought against publication of the Pentagon Papers even though they were bound to embarrass the Democratic Johnson administration far more than Nixon's.

"It involves our allies in various places in the Middle East. It involves our allies in Turkey and in Afghanistan and involves people in our Congress and our State Department," he says.

Yes, Israel and the extremely powerful AIPAC lobby which supports both parties, is said to be involved as well.

"There's no way that the President and Vice-President can escape culpability in this case," Ellsberg charges. "If they claim they don't know about it, then they are culpable in not knowing about it, and that's impeachable right there."

Just as Ellsberg had hoped in 1971, and later encouraged others over the years, Edmonds remains hopeful that somehow, in telling her story --- if she will be allowed tell her story --- it will help others to step forward and do the same.

"Maybe it'll cause other whistleblowers at NSA, FBI...to see that they should come forward and tell what they know," she said in a telephone interview yesterday. "We haven't been seeing them come forward. Maybe it takes just one person to see what's going to happen."

"For now, as you can see," she added, "the fear tactics have worked."

| [+/-] |

Newsweek & Most Media Embraces Karl Rove, After TIME Takes a Pass |

At Radar Online, Charles Kaiser writes:

When Newsweek made Karl Rove one of its columnists last week (along with Markos (Daily Kos) Moulitsas for balance), there was one big question: Could the number of new readers attracted by this fancy new hire possibly exceed the hordes of freshly canceled subscriptions?

The early betting was heavily against any circulation increase. And the odds didn't get better with Rove's first column. His biggest scoop was about the "full-length vanity mirror" found in the West Wing office he inherited from Hillary—and the fact that she had denied putting the mirror there (twice). This, you see, is Rove's idea of "a small but telling story: She is tough, persistent, and forgets nothing." Rove's hiring (which the New York Times didn't even bother to report) makes him the latest in a long and distinguished line of politicos turned pundits who owe their big journalism careers almost entirely to the flowery rhetoric of Spiro T. Agnew.

For latecomers to this never-ending melodrama, Agnew was Richard Nixon's first vice president—the one whose main qualification for the job was this: "No assassin in his right mind would kill me,'' Nixon explained. ''They know if they did that they would wind up with Agnew!" Once Agnew started his blistering attacks on the commie-pinko-liberal press, he became a celebrity in his own right. He called reporters "an effete corps of impudent snobs" and television commentators ''a tiny fraternity of privileged men elected by no one and enjoying a monopoly sanctioned and licensed by the government.''

Since almost all of these haikus were written by conservative White House speechwriters Bill Safire and Pat Buchanan, it was only fitting that they would be among the first to benefit from them.

After a brief push back from shocked newspaper big shots, opposition to Agnew's slanted-media thesis crumbled. In 1973, Nixon alum Bill Safire landed on the op-ed page of the New York Times. (Agnew was actually forced to resign later that same year, after being caught up in a kickback scandal that dated from his tenure as governor of Maryland, but conservatives have continued their nonstop anti-press campaign ever since.) Around the same time, George Will began appearing more regularly in the Washington Post (while still moonlighting as a speechwriter for Jesse Helms). And then came the ubiquitous Pat Buchanan.

The success of Safire, Will, and Buchanan is a good barometer of just how far right you can go in Washington and still remain an honored member of the old boys' club. In his new book about the 1960s, Tom Brokaw explains that Buchanan's "good humor" has made him "enduringly popular even with liberal observers."

That's the genius of Washington—just because you've written that Adolf Hitler was "an individual of great courage" (Google "anti-Semitism of Pat Buchanan" and you get 231,000 hits), dismissed the idea that "white rule of a black majority is inherently wrong" in South Africa, or shown your lavender-friendly side by pointing out that "homosexuality involves sexual acts most men consider not only immoral, but filthy," none of that will prevent you from continuing as a regular on Meet the Press. (And you're surprised that Tim Russert was never offended by Imus?)

For its part, Time magazine said nothing publicly about Rove's arrival at Newsweek, but a well-placed source told me that Bob Barnett (every Washington literati's favorite lawyer, including Bill Clinton) had traveled to the Time-Life building on Sixth Avenue to offer Rove's services before Newsweek snared them. Time's editors apparently felt the cost/benefit analysis wouldn't be in their favor if they embraced the man who has done more than anyone to keep the spirit of Joe McCarthy alive and well in American politics. (Read Joshua Green's definitive profile from the Atlantic in 2004.) "Time thought this wouldn't be like hiring George Stephanopoulos," my source explained. "They think Karl is essentially like an unindicted coconspirator in a whole string of felonies."

Besides the obvious shock value, there was another reason Rove's arrival in the fourth estate was inevitable. In public, Rove is one of dozens of conservatives who assiduously bash the press. Last summer, channeling Agnew, Rove told Rush Limbaugh that "the people I see criticizing [Bush] are sort of elite effete snobs." But at the same time, Rove was constantly massaging big-time Washington journalists over long lunches at the Hay Adams Hotel.

The result of this continuous media handling was a mostly kid-glove treatment of Rove by great Washington political reporters like Anne Kornblut. The day after Rove dodged an indictment by the special prosecutor, this is how Kornblut appraised him in the New York Times: "a cheerful, sharp-witted operative fond of sparring with reporters off the record." It's that kind of hard-hitting approach that got Kornblut stolen away by the Washington Post—but also makes it possible for Jon Stewart to provide an essential reality check on our nation's capital. At the moment, the Daily Show is condemned to reruns for the length of the writers' strike, but last week there was a magnificent moment of serendipity. The same day Newsweek announced its new hire, the show rebroadcast a feature on Rove from the week after he left the White House.

"Washington was very shaken last week," Stewart intoned, "with news that Karl Rove, whose bountiful advisory teats had fed so many Beltway insiders for lo these six and a half years, was capping the spigot and moving on." Then Chris Wallace was shown offering up a list of "Karl Rove's greatest hits." Cut to Stewart:

"I just bought those: John McCain's black baby; Max Cleland, the one-limb pussy; The Queers are coming!; and, of course, Schiavo-a-go-go. No need to call now—your phones have already been tapped.

| [+/-] |

Top Bush Homeland Security Adviser Resigns |

CQ reports:

Frances Fragos Townsend, President Bush’s top homeland security adviser since 2004, has resigned, the White House said Monday.

Townsend joins a laundry list of top-level officials to leave the administration in Bush’s second term, including political guru Karl Rove, press secretary Tony Snow, Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales and Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld.

As assistant to the president for homeland security and counterterrorism, Townsend was a key player in the administration’s efforts to fight terrorism.

“Fran has always provided wise counsel on how to best protect the American people from the threat of terrorism,” Bush said in a statement. “We are safer today because of her leadership.”

White House spokeswoman Dana Perino said Townsend has been discussing her departure with the president for months, and left to “pursue some private-sector opportunities.

“She does intend to remain very active in the public debate about counterterrorism, and especially the tools that she believes policymakers and the intelligence community and the Justice Department officials and others across the government need in order to beat back the very determined enemy that we face,” Perino said.

She said no replacement has been named, and Townsend would stay at her post through the holiday season.

Sunday, November 18, 2007

| [+/-] |

Love in the Time of Dementia |

So this, in the end, is what love is.

The NY Times reports:

Former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s husband, suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, has a romance with another woman, and the former justice is thrilled — even visits with the new couple while they hold hands on the porch swing — because it is a relief to see her husband of 55 years so content.

What culture tells us about love is generally young love. Songs and movies and literature show us the rapture and the betrayal, the breathlessness and the tears. The O’Connors’ story, reported by the couple’s son in an interview with a television station in Arizona, where Mr. O’Connor lives in an assisted-living center, opened a window onto what might be called, for comparison’s sake, old love.

Of course, it illuminated the relationships that often develop among Alzheimer’s patients — new attachments, some call them — and how the desire for intimacy persists even when dementia steals so much else. But in the description of Justice O’Connor’s reaction, the story revealed a poignancy and a richness to love in the later years, providing a rare model at a time when people are living longer, and loving longer.

“This is right up there in terms of the cutting-edge ethical and cultural issues of late life love,” said Thomas R. Cole, director of the McGovern Center for Health, Humanities and the Human Spirit at the University of Texas, and author of a cultural history of aging. “We need moral exemplars, not to slavishly imitate, but to help us identify ways of being in love when you’re older.”

Historically, love in older age has not been given much of a place in culture, Dr. Cole said. It once conjured images that were distasteful or even scary: the dirty old man, the erotic old witch.

That is beginning to change, Dr. Cole said, as life expectancy increases, and a generation more sexually liberated begins to age. Nursing homes are being forced to confront an increase in sexual activity.

And despite the stereotypes, researchers who study emotions across the life span say old love is in many ways more satisfying than young love — even as it is also more complex, as the O’Connors’ example shows.

“There’s a difference between love as it is presented in movies and music as this jazzy sexy thing that involves bikini underwear and what love actually turns out to be,” said the psychologist Mary Pipher, whose book “Another Country” looked at the emotional life of the elderly. “The really interesting script isn’t that people like to have sex. The really interesting script is what people are willing to put up with.”

“Young love is about wanting to be happy,” she said. “Old love is about wanting someone else to be happy.”

That’s one way to look at it, at any rate. And it’s not just that relationships are seasoned by time and shared memories — although that’s part of it, as is the inertia the researchers call the familiarity effect, which keeps people from leaving a longtime relationship even though he nags and she won’t ask for directions.

It’s also that brain researchers say older people may simply be better able to deal with the emotional vicissitudes of love. As it ages, the brain becomes more programmed to be happy in relationships.

Researchers trying to understand aging and emotion performed brain scans on people across a range of ages, gauging their reactions to positive and negative scenes. Young people tended to respond to the negative scenes. Those in middle age took in a better balance of the positive. And older people responded only to the positive scenes.

“As people get older, they seem to naturally look at the world through positivity and be willing to accept things that when we’re young we would find disturbing and vexing,” said John Gabrieli, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and one of the researchers.

It is not rationalization: the reaction is instantaneous. “Instead of what would be most disturbing for somebody, feeling betrayed or discomfort, the other thoughts — about how from his perspective it’s not betrayal — can be accommodated much more easily,” Dr. Gabrieli said. “It paves the way for you to be sympathetic to the situation from his perspective, to be less disturbed from her perspective.”

Young brains tend to go to extremes — the swooning or sobbing so characteristic of young love. Old love puts things in soft focus.

“As you get older you begin to recognize that this isn’t going to last forever, for better or for worse,” said Laura L. Carstensen, director of the Stanford Center on Longevity and a research counterpart of Dr. Gabrieli’s in the brain imaging research. “You understand that the bad times pass, and you understand that the good times pass,” Dr. Carstensen said. “As you experience them, they’re more precious, they’re richer.”

Of course, not everyone would show the emotionally generous response that Justice O’Connor did. As Dr. Cole said, “I have many examples in my mind of people who are just as jealous, just as infantile, just as filled with irrationality when they fall in love in their 70s and 80s as she is self-transcendent.”

And it still is possible to have a broken heart in old age. But in general, Dr. Carstensen said: “A broken heart looks different in somebody old. You don’t yell and scream and cry all day long like you might if you were 20.”

In one of the few cultural examples exploring old love — the film “Away From Her,” based on an Alice Munro short story and released in the spring — the starting point is similar to the O’Connors’ story. A man who cannot imagine life without his sparkling wife of some decades watches her slip into Alzheimer’s and then a romance with another patient in a nursing home. In the fictional example, the spousal devotion is such that he arranges for her new boyfriend to return to the nursing home after seeing how crushed she is when the man moves away.

But the story is more complex. The husband had a series of affairs years earlier, so what seems like devotion is also a desire to pay her back and to ease his own remorse.

For Olympia Dukakis, whose mother had Alzheimer’s and who played the wife of the other man in the film, that wrinkle explains the resonance of Ms. Munro’s story.

“She was very aware that contradictory things live together,” Ms. Dukakis said. “You can’t look at it and say he did it purely for love. It’s a complicated issue, because there’s a lot of life that has been lived. It’s not going to be simple.”

Still, for all those kinds of complications, those who study aging can only smile at young lovers who say they never want to become like an old married couple. Despite the popular preference for young love, the O’Connors’ example suggests that we should all aspire to old love, for better and for worse.

“Young love is very privileged, and as a culture that may be a mistake,” Dr. Pipher said. “If you want a communal culture where people make sacrifices for each other and work for the common good, you would have a culture that privileges the stories of older people.”

Those stories would not be without their troubles. But nor would they be without rewards. “If you stay married,” Dr. Pipher said, “there’s riches in store that nobody 25 years old can imagine.”

Saturday, November 17, 2007

| [+/-] |

Robert Novak: Hillary's Dirt on Obama |

Robert Novak writes:

Agents of Sen. Hillary Clinton are spreading the word in Democratic circles that she has scandalous information about her principal opponent for the party's presidential nomination, Sen. Barack Obama, but has decided not to use it. The nature of the alleged scandal was not disclosed.