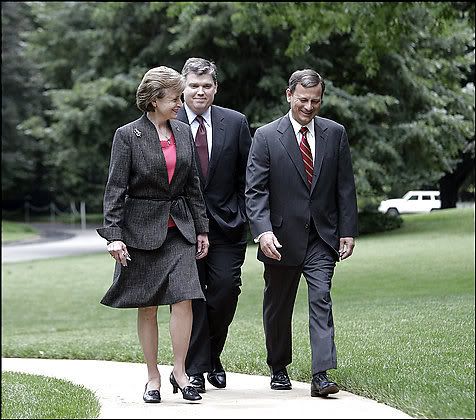

New Book Looks Inside Bush Controversies Harriet Miers with John G. Roberts Jr., right, and an unidentified person in July 2005. A new book, "Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush," describes how Bush came to nominate Miers for the Supreme Court. (By Eric Draper -- The White House Via Getty Images)

Harriet Miers with John G. Roberts Jr., right, and an unidentified person in July 2005. A new book, "Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush," describes how Bush came to nominate Miers for the Supreme Court. (By Eric Draper -- The White House Via Getty Images)

The Washington Post reports:

John G. Roberts Jr., now the chief justice of the United States, suggested Harriet Miers to President Bush as a possible Supreme Court justice, according to a new book on the Bush presidency.

Miers, the White House counsel and a Bush loyalist from Texas, did not want the job, but Bush and first lady Laura Bush prevailed on her to accept the nomination, journalist Robert Draper writes in "Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush."

Karl Rove, Bush's top political adviser, raised concerns about the selection but was "shouted down" and subsequently muted his objections, while other advisers did not realize the outcry it would cause within the president's conservative political base, Draper writes.

The nomination of Miers was one of several self-inflicted wounds that have damaged the Bush presidency during its second term. After Miers withdrew in the face of the conservative furor, Samuel A. Alito Jr. was selected and confirmed for the seat.

In recounting this and other controversies of Bush's tenure, Draper offers an intimate portrait of a White House racked by more infighting than is commonly portrayed and of a president who would, alternately, intensely review speeches line by line or act strangely disengaged from big issues.

Draper, a national correspondent for GQ, first wrote about Bush in 1998, when he was the Texas governor. He received unusual cooperation from the White House in preparing "Dead Certain," which will hit bookstores tomorrow. In addition to conducting six interviews with the president, Draper said he also interviewed Rove, Vice President Cheney, Laura Bush and many senior White House and administration officials.

Draper writes that Bush was "gassed" after an 80-minute bike ride at his Crawford, Tex., ranch on the day before Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast and was largely silent during a subsequent video briefing from then-FEMA director Michael D. Brown and other top officials making preparations for the storm.

He also reports that the president took an informal poll of his top advisers in April 2006 on whether to fire Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld.

During a private dinner at the White House to discuss how to buoy Bush's presidency, seven voted to dump Rumsfeld, including Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, incoming chief of staff Joshua B. Bolten, the outgoing chief, Andrew Card, and Ed Gillespie, then an outside adviser and now White House counselor. Bush raised his hand along with three others who wanted Rumsfeld to stay, including Rove and national security adviser Stephen J. Hadley. Rumsfeld was ousted after the November elections.

The book offers more than 400 footnotes, but Draper does not make clear the sourcing for some of the more arresting assertions -- such as the one about Roberts's role in the Miers nomination, which has hitherto not come to light. Roberts's nomination was highly praised by conservatives, and they criticized Miers as lacking conservative credentials.

White House spokesman Tony Fratto said yesterday that he had no comment on the book, including the claim about the Miers nomination. Roberts could not be reached for comment, a Supreme Court spokeswoman said last night.

Draper offers some intriguing details about Bush's personal habits, such as his intense love of biking. He reports that White House advance teams and the Secret Service "devoted inordinate energy to satisfying Bush's need for biking trails," descending on a town a couple of days before the president's arrival to find secluded hotels and trails the boss would find challenging.

He also makes new disclosures about the behind-the-scenes infighting at the White House that helped prompt the change from Card to Bolten in the spring of 2006. By that point, he reports, some close to the president had concluded that "the White House management structure had collapsed," with senior aides Rove and Dan Bartlett "constantly at war."

He quotes Gillespie as telling one Republican while running interference for Alito's Supreme Court nomination: "I'm going crazy over here. I feel like a shuttle diplomat, going from office to office. No one will talk to each other."

It has been previously reported that Card first suggested he be replaced to help rejuvenate the White House. But Draper writes that Bush settled on Bolten, then director of the Office of Management and Budget, as the new chief of staff before telling Card. When Card congratulated Bolten on his new assignment, he writes, Bolten "could tell that Card was somewhat surprised and hurt that Bush had moved so swiftly to select a replacement."

Rove, meanwhile, was not happy, Draper writes, with Bolten's decision to strip him of his oversight of policy at the White House, directing his focus instead to politics and the coming midterm elections. Bolten noticed that other staffers were "intimidated" by Rove, and Rove was seen as doing too much, "freelancing, insinuating himself into the message world . . . parachuting into Capitol Hill whenever it suited him."

Draper's book also tackles the run-up to the 2000 election and the administration's handling of Iraq.

He writes that Rove told Bush it was a bad idea to select Cheney as his vice president: "Selecting Daddy's top foreign-policy guru ran counter to message. It was worse than a safe pick -- it was needy." But Bush did not care -- he was comfortable with Cheney and "saw no harm in giving his VP unprecedented run of the place."

Draper offers little additional insight or details of Cheney's large influence in administration policy. But he writes that, despite his air of unflappability, the vice president did find himself ruminating over mistakes made, chief among them installing L. Paul Bremer and the Coalition Provisional Authority to run Iraq for a year after the invasion. Instead, Draper suggests, Cheney believes that the White House should have set up a provisional government right away, as Ahmed Chalabi's Iraqi National Congress recommended from the beginning.

Several of Bush's top advisers believe that the president's view of postwar Iraq was significantly affected by his meeting with three Iraqi exiles in the Oval Office several months before the 2003 invasion, Draper reports.

He writes that all three exiles, Kanan Makiya, Hatem Mukhlis and Rend Franke, agreed without qualification that "Iraq would greet American forces with enthusiasm. Ethnic and religious tensions would dissolve with the collapse of Saddam's regime. And democracy would spring forth with little effort -- particularly in light of Bush's commitment to rebuild the country."

Rove assured Bush, Draper reports, that he had known nothing about Valerie Plame, a CIA operative whose covert status was revealed by administration officials to reporters after Plame's husband criticized the administration's case for war in Iraq. "When Bush learned otherwise," he said, "he hit the roof."

Bush considered whether to cooperate with the book for several months, Draper reports. The two men met for the first time on Dec. 12, 2006, and at the conclusion, the president agreed to another interview. In one of the interviews, he looked ahead to his looming post-presidency, talking of his plans to build an institute focused on freedom and to "replenish the ol' coffers" by giving paid speeches.

He told Draper he could see himself shuttling between Dallas and Crawford. Noting that he ran into former president Bill Clinton at the United Nations last year, Bush added, "Six years from now, you're not going to see me hanging out in the lobby of the U.N."

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Reference materials' site for The Constant American.

Latest From CNN

Must Reading

- Life Inc.: How The World Became a Corporation and How To Take It Back by Douglas Rushkoff

- The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How The War on Terror Turned into a War on American Ideals by Jane Mayer

- Torture Team: Rumsfeld's Memo and the Betrayal of American Values by Philippe Sands

- Class 11: Inside the CIA's First Post-9/11 Spy Class by T.J. Waters

- The Terror Dream: Fear and Fantasy in Post-9/11 American by Susan Faludi

- The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism by Naomi Klein

- A Pretext for War: 9/11, Iraq, and the Abuse of America's Intelligence Agencies by James Bamford

- The Italian Letter: How the Bush Administration Used a Fake Letter to Build the Case for War in Iraq by Peter Eisner

- Blue Covenant: The Global Water Crisis and the Coming Battle for the Right to Water by Maude Barlow

- The One Percent Doctrine by Ron Suskind

- Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic (American Empire Project) by Chalmers Johnson

- Free Lunch: How the Weathiest Americans Enrich Themselves at Government Expense (and Stick You with the Bill) by David Cay Johnston

- You Have No Rights: Stories of America in an Age of Repression by Matthew Rothschild

- What We Say Goes: Conversations on U.S. Power in a Changing World by Noam Chomsky, David Barsamian

- Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking by Malcolm Gladwell

- Blackwater: The Rise of the World's Most Powerful Mercenary Army by Jeremy Scahill

- Whose Freedom?: The Battle Over America's Most Important Idea by George Lakoff

- Blue Gold: The Fight to Stop the Corporate Theft of the World's Water by Maude Barlow and Tony Clarke

- Don't Think of an Elephant: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate--The Essential Guide for Progressives by George Lakoff

- Perfectly Legal: The Covert Campaign to Rig Our Tax System to Benefit the Super Rich--and Cheat Everybody Else by David Cay Johnston

- The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference by Malcolm Gladwell

- Unequal Protection: The Rise of Corporate Dominance and the Theft of Human Rights by Thom Hartmann

- Secrecy & Privilege | Neck Deep

- The Unwanted Gaze: The Destruction of Privacy in America by Jeffrey Rosen

- The October Surprise Mystery

- The Seven Sisters: The great oil companies & the world they shaped

- People's History of the United States by Howard Zinn

- The Student As Nigger by Jerry Farber

Bright Ideas

********************************

Energy Generating Dance Floor

******************************** Stop Junk Mail

********************************

C O N T R I B U T O R S

- Maeven

Blogs on Military Intelligence

Iraq & Afghanistan

Reference Sites

Reference Files

Document File

- [alternative address]

- Analysis-How to train death squads and quash revolutions from San Salvador to Iraq

- Foreclosed: State of the Dream 2008

- Memorandum: Construction Workers Camp at the New Embassy Compound, Baghdad

- OLC Torture Memo-May 10, 2005 (20 pages)

- OLC Torture Memo-May 10, 2005 (46 pages)

- OLC Torture Memo-May 2002

- OLC Torture Memo-May 30, 2005 (40 pages)

- Questions Raised about the Conduct of the State Department Inspector General

- The First Report of the Congressional Oversight Panel for Economic Stabilization

- U.S. Army memo: Collecting Information on U.S. Persons

- U.S. Army: Civilian Inmate Prison Camps on Army Installations

- U.S. CounterInsurgency Manual

- U.S. CounterInsurgency Manual-1994 Version

- U.S. Special Forces CounterInsurgency Manuel - WikiLeaks

Climate Change

What"s Up In The Universe?

Let's Go To The Movies!

[+/-] expand/collapse

Life Inc., The Movie

James Burke's After The Warming

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 1 of 7 Noam Chomsky vs Alan Dershowitz

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 2 of 7 Noam Chomsky vs Alan Dershowitz

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 3 of 7 Noam Chomsky vs Alan Dershowitz

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 4 of 7 Noam Chomsky vs Alan Dershowitz

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 5 of 7 Noam Chomsky vs Alan Dershowitz

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 6 of 7 Noam Chomsky vs Alan Dershowitz

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 7 of 7 "Distorted Morality," a lecture by Noam Chomsky: Noam Chomsky on BookTV, 4/17/07, Part 1: Noam Chomsky on BookTV, 4/17/07, Part 2: Noam Chomsky at MIT, "The Militarization of Science and Space": Noam Chomsky's "Manufacturing Consent": 9/11 Truth: Unusual Evacuations

* * * * * * *

Torturing Democracy* * * * * * *

Peace, Propaganda and the Promised Land The Revolution Will Not Be Televised - The Smartest Guys in the RoomEnron

Posted Jun 08, 2006Full Version

Iraq's Missing Billions War Made Easy The Big Buy - The Rise and Fall of Tom Delay Iraq: The Hidden Story Iraq For Sale - a Robert Greenwald film The Secret Government - PBS, Bill Moyers The History of Oil - Robert Newman The Power of Nightmares "Confessions of an Economic Hitman," an interview with the author, John Perkins: "America: Freedom to Fascism," a film by Aaron Russo: Greg Palast, "How Bush Stole The 2000 Election," Part 1 of 2: Sir, No Sir! Greg Palast, "How Bush Stole The 2000 Election," Part 2 of 2: Noam Chomsky vs Alan DershowitzIsrael And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 1 of 7 Noam Chomsky vs Alan Dershowitz

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 2 of 7 Noam Chomsky vs Alan Dershowitz

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 3 of 7 Noam Chomsky vs Alan Dershowitz

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 4 of 7 Noam Chomsky vs Alan Dershowitz

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 5 of 7 Noam Chomsky vs Alan Dershowitz

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 6 of 7 Noam Chomsky vs Alan Dershowitz

Israel And Palestine After Disengagement: "Where Do We Go From Here?"

Harvard University 11/29/05

Part 7 of 7 "Distorted Morality," a lecture by Noam Chomsky: Noam Chomsky on BookTV, 4/17/07, Part 1: Noam Chomsky on BookTV, 4/17/07, Part 2: Noam Chomsky at MIT, "The Militarization of Science and Space": Noam Chomsky's "Manufacturing Consent": 9/11 Truth: Unusual Evacuations

ExperiLabels [+/-]

- 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (1)

- 110th Congress (1)

- 1949 Geneva Conventions (4)

- 1949 Geneva Conventions-Fourth (1)

- 1949 Geneva Conventions-Third (1)

- 501 (c) (4) (1)

- 60 Minutes (1)

- 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (1)

- 9/11/01 (34)

- 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (2)

- Aaron Mate (1)

- Abd al-Rahim al-Nahsiri (1)

- Abdul-Mahdi (1)

- abortion (10)

- Abu Dhabi (1)

- Abu Ghraib (19)

- Abu Zubaydah (2)

- ACLU (3)

- activism (3)

- acts of misdirection? (3)

- Admiral Michael Mullen (1)

- advisory Board (1)

- Afghan civilians (1)

- Afghanistan (10)

- Ahmed Chalabi (1)

- Al Gore (4)

- Al Kamen (1)

- Al Qaeda (16)

- Al Sharpton (4)

- al-Hashemi (2)

- al-Mahdi (1)

- al-Maliki (11)

- al-Sistani (1)

- Alabama (3)

- Alan Greenspan (1)

- Alan Mollohan (1)

- Alan Simpson (1)

- Alaska (10)

- Alberto Gonzales (26)

- Alberto Mora (1)

- Alfa Group (1)

- Alphonse D'Amato (1)

- alternative media (1)

- amendment 2073 (1)

- American culture (49)

- American Petroleum Institute (1)

- Amy Goodman (7)

- An Inconvenient Truth (1)

- Analysis Corp (1)

- Anbar (3)

- Andrea Mitchell (1)

- Andrew Card (5)

- animals (15)

- Another Bush cock-up (4)

- Anthony Cordesman (1)

- Anthony Kennedy (1)

- Anthony Zinni (1)

- anthrax (6)

- antiquities (1)

- Antonia Juhasz (2)

- AQI (1)

- Arent Fox Kintner Plotkin and Kahn (1)

- Ari Fleischer (1)

- Arizona (3)

- Arkansas (1)

- Arlen Specter (14)

- arms sales (3)

- Armstrong Williams (3)

- Arnold Schwarzenegger (1)

- art (3)

- asbestos (2)

- Atlanta (1)

- audio (2)

- AUMF 2002 (1)

- Australia (1)

- Bab al-Sheik (1)

- Baghdad (1)

- Bagram (1)

- bailout (4)

- Bakhtawar Zardari (1)

- Bangladesh (1)

- Baqouba (1)

- Barack Obama (43)

- Barbara Bush (5)

- Barry Jackson (1)

- Basra (2)

- BCCI (2)

- Bearing Point (1)

- bees (2)

- Ben Bernanke (1)

- Ben Nelson (2)

- Benazir Bhutto (7)

- benchmarks (3)

- Benita Fitzgerald Mosley (2)

- Benjamin Netanyahu (1)

- Big Agra (7)

- Big Business (2)

- Big Oil (12)

- Big Pharma (1)

- BigAgra (1)

- Bilawal Bhutto (2)

- Bill Clinton (19)

- Bill Clinton was no friend to liberals (1)

- Bill Gates (1)

- Bill Keller (1)

- Bill Kristol (2)

- Bill Maher (1)

- Bill Moyers (2)

- Bill Richardson (3)

- Bill Sammon (2)

- birds (1)

- Blackstone (2)

- Blackwater (11)

- blogging (4)

- Bob Baer (2)

- Bob Corker (1)

- Bob Graham (1)

- Bob Perry (1)

- Bob Shrum (1)

- Bobby Jindal (2)

- Bolivia (1)

- books (30)

- boys will be boys (1)

- BP (4)

- BP America (1)

- BP PLC (1)

- Brad Delong (1)

- Bradley Schlozman (1)

- Brazil (1)

- Bremer's 100 Orders (2)

- Brent Scowcroft (3)

- Brewster Jennings (1)

- Brian Schweitzer (1)

- Brigadier General Janis Karpinski (3)

- Bruce Bartlett (1)

- Bruce Fein (1)

- Bruce McMahan (2)

- Bud Cummins (1)

- Bulgaria (1)

- Bureau of Diplomatic Security (1)

- Burma (3)

- Bush (89)

- Bush 1 administration (2)

- Bush administration (98)

- Bush family (2)

- Bush veto (4)

- Bush-speak (1)

- Bush's legacy (5)

- Bush's surge (38)

- CAFTA (1)

- California (20)

- Cambodia (1)

- Camp Bucca (2)

- Camp Cropper (1)

- campaign contributors (1)

- Canada (1)

- cancer (1)

- candidates' positions (1)

- capitalism (3)

- Carl Levin (4)

- Carl Lindner (1)

- Carlyle Group (3)

- Carol Lam (1)

- Caroline Cheeks Kilpatrick (1)

- CBO (1)

- CBS (3)

- celebrity gossip (2)

- censorship (3)

- Centers for Disease Control (1)

- Chad (1)

- Chalmers Johnson (1)

- Charles Duelfer (2)

- Charles Grassley (6)

- Charles Koch (2)

- Charlie Rangel (1)

- charts (1)

- Chechnya (1)

- chemical industry (1)

- Chevron (3)

- ChevronTexaco (1)

- Chicago (2)

- children (1)

- China (12)

- Chip Reid (1)

- Chris Dodd (4)

- Chris Hedges (1)

- Chris Matthews (10)

- Chris Van Hollen (2)

- Christian Coalition (1)

- Christine Todd Whitman (3)

- Christopher Hitchens (1)

- Chuck Schumer (9)

- CIA (36)

- CIA leak investigation (4)

- CIA tapes (1)

- Cindy Sheehan (3)

- Citibank (1)

- civil liberties (4)

- civil rights (5)

- Claire McCaskill (1)

- Clarence Page (2)

- Clarence Thomas (1)

- Cleveland (1)

- climate change (8)

- Clinton administration (2)

- cluster bombs (3)

- CNN (1)

- coal (2)

- Coalition Provisional Authority (4)

- Cofer Black (2)

- Cold War (2)

- Colin Powell (5)

- Colleen Rowley (3)

- Colombia (1)

- Colonel Thomas M. Pappas (3)

- Colorado (3)

- Condoleeza Rice (5)

- Congo (1)

- Congressional Record (1)

- Connecticut (1)

- Conoco (1)

- ConocoPhillips (1)

- Conservatives (5)

- conspicuous consumption (12)

- Contempt of Congress (2)

- contractors (17)

- corn (5)

- corporate welfare (1)

- corruption (27)

- Council for National Policy (4)

- Council on Foreign Relations (1)

- CPA (9)

- Craig Crawford (2)

- Craig Fuller (1)

- Craig Thomas (1)

- crumbling infrastructure (1)

- Cuba (11)

- culture (22)

- Curveball (1)

- Cynthia Tucker (1)

- Cyril Wecht (1)

- Czech Republic (1)

- D and E/D and X/Partial Birth Abortion (2)

- D.C. voting rights (1)

- Dan Abrams (1)

- Dan Bartlett (2)

- Dan Burton (1)

- Dan Metcalfe (1)

- Dan Rather (1)

- Daniel Ellsberg (2)

- Daniel Inouye (1)

- Darrell Issa (2)

- David Addington (1)

- David Albright (2)

- David Broder (1)

- David Brooks (1)

- David Frum (1)

- David Gergen (2)

- David Gregory (8)

- David Gribben (1)

- David Horgan (1)

- David Kay (1)

- David Koch (2)

- David M. McIntosh (1)

- David MacMichael (2)

- David Rivkin (1)

- David Shuster (1)

- David Vitter (6)

- death penalty (2)

- death toll (1)

- debates (5)

- Debra Wong Yang (1)

- Defense Appropriations Subcommittee (1)

- Defense Authoriation Act of 2006 (1)

- Defense Policy Board (1)

- Deforest Soaries (3)

- Democracy Now (11)

- Democratic Party (4)

- Democratic Presidential debates (2)

- Democrats (9)

- Democrats suck too (39)

- Denmark (2)

- Dennis Kucinich (3)

- Department of Homeland Security (3)

- deregulation (17)

- derivatives (1)

- Det Norske Oljeselskap (1)

- detainees (2)

- Detroit (2)

- Diane Beaver (1)

- Dianne Feinstein (7)

- Dick Cheney (37)

- Dick Cheney's energy task force (4)

- Dick Durbin (4)

- Dick Lugar (2)

- dirty tricks (17)

- dissent (1)

- Diyala (1)

- DLC politics (1)

- DNO (2)

- documents (1)

- DoD (1)

- dogs (2)

- DOJ (5)

- domestic spying (1)

- Don Evans (4)

- Don Imus (6)

- Don Siegelman (1)

- Donald Rumsfeld (12)

- Douglas Brinkley (1)

- Douglas Feith (4)

- Dr. Justin Frank (1)

- draft (2)

- Drew Westen (1)

- drought (2)

- drug bill (1)

- drugs-illicit (4)

- drugs-pharmaceutical (1)

- Duncan Hunter (1)

- E.J. Dionne (1)

- earmarks (4)

- Ebay (1)

- economics (23)

- economy (81)

- Ecuador (1)

- Ed Markey (1)

- Ed Rogers (1)

- education (5)

- Egypt (2)

- Ehud Olmert (1)

- El Salvador (2)

- election 1980 (1)

- election 1992 (1)

- election 2000 (8)

- election 2002 (1)

- election 2008 (45)

- election reform (4)

- elections 2002 (2)

- elections 2004 (1)

- elections 2006 (4)

- elections 2008 (76)

- elections 2012 (1)

- electionws 2004 (1)

- Elian Gonzalez (1)

- Elijah Cummings (1)

- Elizabeth Dole (1)

- Ellen Tauscher (1)

- Elliot Abrams (1)

- email (4)

- ENDGAME (1)

- endorsements (3)

- energy (13)

- energy nuclear (2)

- energy nuclear (1)

- energy policy (6)

- entertainment (7)

- environment (59)

- environmental (1)

- EPA (3)

- Eric Edelman (1)

- Eric Holder (1)

- Eric Prince (2)

- Estonia (1)

- ethanol (1)

- ethics (2)

- Eugene Robinson (2)

- European Union (1)

- executive order 12334 (1)

- executive order 12472 (1)

- executive order 12656 (1)

- executive order 12958 (1)

- executive order 13228 (1)

- executive order 13233 (2)

- executive order 13303 (1)

- executive order 13315 (1)

- executive order 13350 (1)

- executive orders (8)

- Executive Privilege (4)

- Exxon (1)

- ExxonMobil (5)

- Fairness Doctrine (1)

- faith-based organizations (2)

- Fallujah (2)

- Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (1)

- Farm Bill (5)

- Faye Williams (1)

- FBI (16)

- FCC (2)

- FDA (6)

- FDIC (1)

- FEC (1)

- Federal Reserve (4)

- Federalist Society (1)

- FEMA (1)

- filibuster (1)

- financial disclosure (1)

- first amendment (11)

- FISA bill (13)

- fish (3)

- flat tax (1)

- FOIA (1)

- food (46)

- For the children (2)

- For the common good (2)

- Foreign Intelligence cronyism (1)

- fourth amendment (1)

- Fox News (1)

- France (2)

- Frances Townsend (2)

- Frank Murkowski (1)

- Frank Rich (1)

- Frank Riggs (1)

- Fred Fielding (2)

- Fred Koch (1)

- Fred Thompson (15)

- free speech (3)

- free trade (1)

- freedom and democracy in Iraq (6)

- Freedom of Information Act of 2007 (1)

- Freedom to dissent...NOT (1)

- Freedom's Watch (2)

- Frontline (1)

- FUBAR (7)

- Futile Care Law (1)

- Gail Norton (2)

- GAO (7)

- gay rights (3)

- Gaza (2)

- Gazprom (1)

- gender inequality (4)

- Genel Enerji (1)

- General David Petraeus (6)

- General Electric (1)

- General Eric Shenseki (1)

- General Michael Hayden (6)

- General Tommy Franks (1)

- George H.W. Bush (10)

- George Lakoff (1)

- George P. Bush (1)

- George Tenet (15)

- George Voinovich (1)

- Georgia (7)

- Georgia Maryland (1)

- Georgia Pacific Corp. (1)

- Georgia Thompson (1)

- Germany (4)

- Getting To Know Your Adversary (1)

- Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 (1)

- Glenn Greenwald (1)

- global warming (20)

- globalization (2)

- GMO (2)

- Gonzales vs. Carhart (1)

- GOP (12)

- Gordon Brown (2)

- Governor Jim Doyle (1)

- Great Britain (22)

- Greg Thielmann (1)

- Grover Norquist (3)

- Guantanamo (20)

- Guatemala (1)

- Gulf of Mexico (2)

- Gulf War 1 (3)

- guns (2)

- H.R. 1255 (1)

- H.R. 1591 (1)

- H.R. 2206 (1)

- H.R. 3222 (1)

- H.R. 4156 (1)

- H.R. 4241 (1)

- Hague Regulations of 1907 (3)

- Haiti (1)

- Haley Barbour (1)

- Halliburton (6)

- Hamid Karzai (1)

- Hardball (16)

- Harold Ford Jr. (1)

- Harold Ickes (1)

- Harold Simmons (1)

- Harriet Miers (4)

- Harry Reid (9)

- Hatch Act (1)

- Hawaii (1)

- health (65)

- health care reform (1)

- health insurance (6)

- hearings (1)

- hedge fund managers (2)

- hedge funds (2)

- Helms-Burton Act (1)

- Henry Kissinger (1)

- Henry Paulson (3)

- Henry Waxman (8)

- Hezbollah (1)

- Hillary Clinton (62)

- holidays (2)

- homeland security (2)

- Homeland Security appropriations bill (1)

- House Appropriations Committee (3)

- House Committee on Intelligence (3)

- House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform (6)

- House Foreign Affairs Committee (1)

- House Judiciary Committee (5)

- House Natural Resources Committee (1)

- House Republicans (6)

- housing (1)

- Howard Fineman (3)

- Howard Wolfson (1)

- HR 1955 (1)

- HSPD 20 (2)

- Huffington Post (1)

- Hugo Chavez (2)

- human rights (13)

- Hungary (1)

- Hurricane Katrina (2)

- Hypocrisy 101 (4)

- Idaho (1)

- Ideas Whose Time Has Come? (1)

- illegal immigration (7)

- Illinois (3)

- IMF (4)

- impeachment (12)

- implosions (10)

- In our names (19)

- India (1)

- Indiana (4)

- Indonesia (1)

- insurgency (1)

- intelligence (9)

- Internet (7)

- interviews (19)

- Invocon (1)

- Iowa (3)

- IPO (1)

- Iran (27)

- Iran-Contra (1)

- Iran-Iraq war (1)

- Iraq (42)

- Iraq czar (1)

- Iraq elections (2)

- Iraq Health Ministry (1)

- Iraq occupation (2)

- Iraq Petroleum Company (1)

- Iraq reconstruction (5)

- Iraq Study Group (1)

- Iraq Survey Group (2)

- Iraqi army (1)

- Iraqi civilians (13)

- Iraqi Islamic Party (1)

- Ireland (1)

- Ishaqi (1)

- Islam (1)

- Israel (18)

- Issam Al-Chalabi (1)

- Italy (1)

- Iyad Allawi (1)

- Jack Abramoff (1)

- Jack Reed (2)

- James Baker (2)

- James Carville (3)

- James Comey (6)

- James Dobson (1)

- James Inholfe (1)

- James K. Haveman (1)

- James Schlesinger (1)

- James Sensenbrenner (1)

- James Woolsey (3)

- James Yousef Yee (1)

- Jan Schakowsky (1)

- Jane Dalton (1)

- Jane Harman (3)

- Japan (2)

- Jay Dardenne (1)

- Jay Leno (1)

- Jay Rockefeller (6)

- Jean Shaheen (4)

- Jean-Baptiste Aristide (1)

- Jean-Bertrand Aristide (1)

- Jeff Sessions (3)

- Jeffrey Toobin (1)

- Jennifer Fitzgerald (1)

- Jeremy Scahill (3)

- Jerrold Nadler (2)

- Jerry Lewis (1)

- Jesse Helms (1)

- Jesse Jackson (1)

- Jill Abramson (1)

- Jim Bunning (1)

- Jim DeMint (2)

- Jim Donelon (1)

- Jim Gilmore (1)

- Jim Hightower (2)

- Jim Marcinkowski (1)

- Jim McCrery (1)

- Jim McGovern (1)

- Jim Miklaszewski (1)

- Jim Moran (1)

- Jim O'Beirne (2)

- Jim Rogers (3)

- Jim VandeHei (1)

- Jim Webb (2)

- Jimmy Breslin (1)

- Jimmy Carter (1)

- Jo Ann Emerson (1)

- Joan Baez (1)

- Joe Allbaugh (1)

- Joe Biden (4)

- Joe Conason (3)

- Joe DiGenova (2)

- Joe Klein (1)

- Joe Lieberman (5)

- Joe Scarborough (1)

- Joe Wilson (9)

- John Ashcroft (7)

- John B. Taylor (1)

- John Barrasso (1)

- John Boehner (3)

- John Bolton (1)

- John Conyers (5)

- John Cornyn (1)

- John D. Bates (1)

- John Danforth (1)

- John Dean (2)

- John Dingell (2)

- John Edwards (9)

- John Gilmore (2)

- John Harris (2)

- John Harwood (2)

- John Kerry (3)

- John King (1)

- John McCain (11)

- John Mellencamp (1)

- John Murtha (3)

- John Nichols (2)

- John Roberts (4)

- John Sununu (3)

- John Warner (4)

- John Yoo (1)

- John Zogby (1)

- Joint Chiefs of Staff (2)

- Jon Corzine (1)

- Jonathan Alter (2)

- Jonathan Cohn (1)

- Jonathan Turley (1)

- Jordan (4)

- Jose Padilla (1)

- Joseph Stiglitz (1)

- Josh Bolten (2)

- Judith Miller (2)

- Judith Nathan Giuliani (1)

- K Street (2)

- Kamil Mubdir Gailani (1)

- Karbala (1)

- Karen Hughes (1)

- Karl Rove (25)

- Kate O'Beirne (2)

- Kazakhstan (1)

- Keith Olbermann (6)

- Ken Blackwell (1)

- Ken Mehlman (1)

- Ken Pollack (1)

- Ken Salazar (1)

- Ken Starr (1)

- Ken Wainstein (1)

- Kennedy family (1)

- Kenneth Blackwell (1)

- Kentucky (1)

- Ketchum (1)

- Khalid Sheik Mohammed (1)

- King Abdullah (1)

- Kit Bond (2)

- Kitty Kelley (1)

- knuckle-dragging Americans (1)

- Koch brothers (2)

- Koch Industries (1)

- KRG (1)

- Kristin Breitweiser (1)

- Kurdistan (3)

- Kurdistan Regional Government (2)

- Kurds (7)

- Kyle Sampson (1)

- L-1 Identity Solutions (1)

- Lamar Alexander (2)

- Lancet study (9)

- Lanny Griffith (1)

- Larry Craig (2)

- Larry Ellison (1)

- Larry Johnson (2)

- Larry Lindsey (1)

- Larry Summers (1)

- Larry Wilkerson (1)

- Las Vegas (3)

- Latvia (1)

- Laura Bush (1)

- Laurie David (1)

- Lawrence Korb (1)

- Leandro Aragoncillo (1)

- Lebanon (3)

- Lee Hamilton (1)

- legislation (30)

- Leon Panetta (1)

- Liberals (2)

- Libya (4)

- Lieutenant General Ricardo S. Sanchez (1)

- Lindsay Graham (6)

- Lisa Murkowski (1)

- lobbyists (6)

- Lockerbie (3)

- Lois Romano (1)

- London (1)

- long war (1)

- Loretta Sanchez (1)

- Lou Dubose (1)

- Louisiana (7)

- Lt. Colonel Steven Jordan (2)

- Lt. General Douglas Lute (2)

- Lt. General Martin Dempsey (1)

- Lt. General Ricardo Sanchez (1)

- Lukoil (1)

- Lynndie England (1)

- Madrid bombings (1)

- Mahdi Army (1)

- Mahmoom Khaghani (1)

- Maine (3)

- mainstream media (8)

- Major General Antonio Taguba (1)

- Major General Benjamin R. Mixon (1)

- Major General Geoffrey Miller (11)

- maps (1)

- Margaret Carlson (1)

- Marion Spike Bowman (2)

- Mark Corallo (1)

- Mark McKinnon (1)

- Mark Mix (1)

- Mark Penn (2)

- Mark Pryor (1)

- martial law (1)

- Mary Beth Buchanan (3)

- Mary Cheney (1)

- Mary Landrieu (1)

- Mary Matalin (2)

- Maryland (2)

- Massachusetts (2)

- Matt Brooks (1)

- Matt Cooper (1)

- Matthew Mead (1)

- Maury Wills (1)

- Max Baucus (1)

- media (15)

- Medicaid (1)

- medical ethics (1)

- Meet the Press (4)

- Meghan O'Sullivan (1)

- Mel Sembler (1)

- meltdown (16)

- men (1)

- mental health (11)

- mental illness (6)

- Mexico (4)

- Michael Allan Leach (1)

- Michael Bloomberg (1)

- Michael Chertoff (6)

- Michael Eric Dyson (1)

- Michael Garcia (1)

- Michael Ledeen (1)

- Michael Moore (4)

- Michael Mukasey (13)

- Michael O'Hanlon (2)

- Michael Pollan (7)

- Michael R. Gordon (2)

- Michael Scheuer (2)

- Michael Steele (1)

- Michael Turk (1)

- Michelle Obama (1)

- Michigan (2)

- Mickey Herskowitz (1)

- Middle East (15)

- Mike Barnicle (1)

- Mike Huckabee (9)

- Mike McConnell (3)

- Mike Mullen (1)

- military budget (5)

- Military Commissions Act of 2006 (1)

- military equipment (15)

- Military Industrial Complex (4)

- military tribunals (1)

- Milwaukee (1)

- Minnesota (2)

- Mississippi (2)

- Missouri (1)

- Mitch McConnell (4)

- Mitt Romney (9)

- Molly Ivins (2)

- moments in history (1)

- Monica Goodling (1)

- Monica Lewinsky (1)

- Montana (3)

- Most Ethical Congress (1)

- MoveOn.org (2)

- movies (2)

- MSNBC (3)

- multinational corporations (2)

- Murray Waas (2)

- N. Korea (4)

- NAFTA (3)

- Najaf (1)

- Nancy Pelosi (16)

- Naomi Klein (10)

- Naomi Wolf (1)

- narcissistic personality disorder (1)

- Nat Parry (1)

- National Defense Authorization Act for 2008 (4)

- National Guard (2)

- National Republican Congressional Committee (1)

- National Security (1)

- National Security Archive (2)

- National Security Decision Directive 188 (1)

- Neil Bush (2)

- Nelson Cohen (3)

- Neoconservatives (4)

- Netherlands (1)

- Nevada (1)

- New Afghanistan (3)

- New Hampshire (8)

- New Iraq (51)

- New Jersey (1)

- New Orleans (1)

- New World Order (9)

- New York (7)

- New York Times (5)

- New Yorker (1)

- Newsweek (8)

- Newt Gingrich (2)

- NIE (4)

- NIH (1)

- Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (2)

- No Child Left Behind (1)

- No WMD (2)

- Noam Chomsky (1)

- Norm Coleman (1)

- North Carolina (3)

- Now That Obama's President - What's Left To Do? (1)

- NRC (1)

- NRCC (1)

- NSA (6)

- NSL (2)

- NSPD 51 (2)

- nuclear (12)

- Obama administration (10)

- obituaries (2)

- oceans (4)

- offshoring (1)

- Ohio (3)

- oil (14)

- oil and gas (20)

- oil law (21)

- Oklahoma (1)

- Oliver North (1)

- Olympia Snowe (1)

- OPEC (3)

- Operation Clean Break (1)

- Operation Rescue (1)

- Oprah Winfrey (1)

- Order 37 (2)

- Order 39 (3)

- Order 40 (1)

- Oregon (1)

- organic farming (1)

- organized labor (7)

- Orrin Hatch (1)

- Osama Bin Laden (9)

- outsourcing (1)

- owls (1)

- PACS (1)

- Pakistan (15)

- Pakistan's People's Party (2)

- Palestinians (2)

- Pan Am 103 (2)

- Paris Hilton (2)

- parliamentary procedure (1)

- passportgate (2)

- Pat Buchanan (4)

- Pat Leahy (2)

- Pat Roberts (4)

- Pat Tillman (2)

- Patrick Lang (1)

- Patrick Leahy (10)

- Patrick McHenry (1)

- Patriot Act (12)

- Patty Murray (1)

- Paul Allen (1)

- Paul Bremer (9)

- Paul Craig Roberts (1)

- Paul Eaton (1)

- Paul Krugman (8)

- Paul O'Neill (1)

- Paul Rieckhoff (2)

- Paul Wellstone (1)

- Paul Weyrich (1)

- Paul Wolfowitz (5)

- PDVSA (1)

- Peak oil (2)

- Pennsylvania (4)

- Pentagon (22)

- people (1)

- Pervez Musharraf (10)

- Pete Domenici (1)

- Peter King (1)

- Petoil (1)

- Petrel Resources (1)

- Phil Gingrey (1)

- Phil Giraldi (1)

- Phil Griffin (1)

- Philip Atkinson (1)

- Philip Zelikow (1)

- Phillipines (2)

- photos (66)

- Phyllis Schlafly (1)

- PKK (1)

- Plan B (1)

- PNAC (1)

- Poland (1)

- police brutality (2)

- political fundraising (1)

- political operatives (1)

- polls (4)

- population control (1)

- Porter Goss (2)

- poverty in America (3)

- Presidential candidates (8)

- Presidential Directives (1)

- Presidential pardons (1)

- Presidential Records Act of 1978 (6)

- press releases (1)

- prewar intelligence (1)

- Prince Bandar bin Sultan (2)

- prisons (6)

- privacy (15)

- Privacy Act of 1974 (1)

- private contractors (1)

- private equity (2)

- privatization (20)

- Profiles (11)

- Project Checkmate (1)

- propaganda (4)

- Protect America Act (2)

- PSA (1)

- psychologists (1)

- Psychology Today (1)

- PTSD (1)

- public relations (1)

- Puerto Rico (2)

- Pulitizer prizes (1)

- Putin (3)

- QinetiQ (1)

- Quds (1)

- race card (7)

- Rachel Maddow (3)

- racism (4)

- Rahm Emanuel (1)

- Ramadi (1)

- Ramzi Yousef (1)

- Rand Corporation (2)

- Ray McGovern (6)

- Reagan administration (1)

- real estate (2)

- Reasons not to vote for Republicans (22)

- Reasons we need campaign finance reform (7)

- recess appointment (1)

- red flags (1)

- reference file (1)

- reference papers (1)

- refugees (3)

- religion (3)

- rendition (2)

- reports (1)

- Republican Party (3)

- Republicans (15)

- Richard Armitage (1)

- Richard Baker (1)

- Richard Clarke (1)

- Richard E. Stickler (1)

- Richard Mellon Scaife (2)

- Richard Nixon (2)

- Richard Perle (6)

- Richard Viguerie (1)

- Richard Wolffe (1)

- Rick Santorum (1)

- right-wing organizations (2)

- RNC (7)

- Robert Dreyfuss (1)

- Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (2)

- Robert Fisk (1)

- Robert Gates (9)

- Robert Johnson (1)

- Robert Kuttner (1)

- Robert Mueller (10)

- Robert Novak (3)

- Robert Parry (6)

- Robert Reich (1)

- Rodney Alexander (1)

- Roger Simon (2)

- Roger Stone (2)

- Romania (1)

- Ron Brownstein (2)

- Ron Paul (3)

- Ron Reagan (1)

- Ron Suskind (1)

- Ron Wyden (1)

- Ronald Reagan (3)

- Roslynn Mauskopf (1)

- Royal Dutch Shell (3)

- Royal Dutch/Shell Group of Cos. (1)

- Rudy Giuliani (5)

- Rudy Guiliani (1)

- rule of law (8)

- Rush Holt (1)

- Russ Feingold (2)

- Russell Feingold (1)

- Russell Simmons (1)

- Russia (4)

- Rwanda (1)

- Ryan Crocker (3)

- S. 1927 (4)

- S. 1932 (1)

- S. 2340 (1)

- S. Carolina (4)

- S. Dakota (1)

- S. Korea (1)

- Sabrina D. Harman (1)

- Saddam Hussein (3)

- Sadr City (1)

- SAIC (1)

- Sam Bodman (1)

- Sam Brownback (2)

- Samarra (2)

- San Francisco (4)

- sanctions (1)

- Sandra Day O'Connor (2)

- Sara Taylor (4)

- Sarah Palin (7)

- Sarkozy (1)

- Saudi Arabia (17)

- Savings and Loan crisis (3)

- science (2)

- Scooter Libby (8)

- Scott Ritter (2)

- SEC (1)

- secrecy (12)

- secret government (2)

- secret holds (1)

- secret prisons (4)

- Secret Service (3)

- secular democracy (1)

- Senate Appropriations subcommittee (2)

- Senate Armed Services Committee (3)

- Senate Energy and Commerce Committee (1)

- Senate Ethics Committee (1)

- Senate Finance Committee (2)

- Senate Intelligence Committee (6)

- Senate Judiciary Committee (22)

- Senate Republicans (1)

- senior issues (2)

- Separation of church and state (8)

- Sergeant Michael J. Smith (1)

- Sergeant Santos A. Cardona (1)

- sex (1)

- sex crimes (1)

- Seymour Hersh (7)

- Sheldon Adelson (2)

- Shell Oil (6)

- Sheryl Crow (1)

- Shiite militias (1)

- shrines (2)

- Sibel Edmonds (1)

- Sibiyha Prince (1)

- Sidney Blumenthal (2)

- SIGIR (1)

- signing statements (1)

- Slovakia (1)

- slow food (2)

- socialism (1)

- SOFA (1)

- Spain (2)

- Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction (1)

- special ops (1)

- Specialist Charles Graner (1)

- speeches (2)

- Stephen Cambone (1)

- Stephen Hadley (8)

- Steve Capus (2)

- Steve Fraser (1)

- Steve McMahon (2)

- Steve Scalise (1)

- Steven Biskupic (1)

- Stuart Bowen (1)

- summer reading list (1)

- Sunni (2)

- sunshine laws (1)

- superdelegates (2)

- supplemental appropriations bill (9)

- Susan Collins (2)

- Susan Page (1)

- Susan Ralston (1)

- Swift Boat veterans (1)

- Swift Boat Veterans for Truth (1)

- Syria (13)

- T. Boone Pickens (1)

- Taguba report (2)

- Talabani (2)

- Taliban (2)

- TALON (1)

- TANG (1)

- taxes (1)

- Ted Kennedy (1)

- Ted Olson (1)

- Ted Stevens (2)

- Telecommunications Act (1)

- Telecoms (2)

- Tennessee (1)

- terrorism (12)

- Terrorist Surveillance Program (6)

- Terry McAuliffe (1)

- Terry O'Donnell (1)

- Texas (11)

- Thailand (1)

- The Fellowship (1)

- think tanks (3)

- Thom Hartmann (1)

- Thomas B. Edsall (1)

- Thomas Blanton (1)

- Thomas Edsall (1)

- Thomas J. Collamore (1)

- Thomas M. Tamm (1)

- Tim Geithner (7)

- Tim Griffin (1)

- Tim LaHaye (1)

- Tim Russert (2)

- Tim Ryan (1)

- Timothy P. Berry (1)

- Todd Graves (1)

- Todd Palin (3)

- Tom Allen (1)

- Tom Andrews (1)

- Tom Brokaw (1)

- Tom Coburn (1)

- Tom Coburt (1)

- Tom Daschle (1)

- Tom Davis (4)

- Tom DeLay (2)

- Tom Harkin (1)

- Tom Lantos (1)

- Tom Maertens (1)

- Tom Oliphant (1)

- Tom Tancredo (1)

- Tom Vilsack (1)

- Tommy Chong (1)

- Tony Blair (7)

- Tony Blankley (2)

- Tony Snow (2)

- tort reform (1)

- torture (51)

- Total (1)

- transcripts (47)

- trauma (2)

- Trent Lott (1)

- trial attorneys (1)

- TSA (1)

- Turkey (4)

- Tyler Drumheller (2)

- Tyumen Oil (1)

- U.S. Air Force (1)

- U.S. Army (2)

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (1)

- U.S. Army's Law of Land Warfare (1)

- U.S. Attorney Bill (1)

- U.S. Attorney General (8)

- U.S. Attorneys (23)

- U.S. bases (2)

- U.S. budget (1)

- U.S. Congress (16)

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (5)

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security (13)

- U.S. Department of Justice (3)

- U.S. Department of the Interior (1)

- U.S. Department of Transportation (1)

- U.S. District Court (1)

- U.S. dollar (4)

- U.S. Empire (1)

- U.S. foreign policy (18)

- U.S. House (10)

- U.S. military (62)

- U.S. Senate (13)

- U.S. State Department (6)

- U.S. Supreme Court (3)

- U.S. trade policies (5)

- U.S. Treasury Department (2)

- U.S.A. (1)

- U.S.S.C. (6)

- UAE (2)

- Ukraine (1)

- UN (7)

- UN Human Rights Commission (1)

- UN resolution 1483 (1)

- UN resolution 1546 (1)

- UN Security Council Resolution 687 (1)

- UNCC (1)

- UNICEF (1)

- unitary executive (2)

- Utah (2)

- Vaclav Klaus (1)

- Valerie Jarrett (1)

- Valerie Plame (12)

- Venezuela (2)

- Vermont (1)

- veterans affairs (1)

- VFW (1)

- Vicente Fox (1)

- video (26)

- video links (1)

- videos (21)

- Vince Cannistraro (1)

- Violence in America (1)

- Virginia (6)

- Vivian Stringer (1)

- voter caging (1)

- voter fraud (5)

- voter ID (3)

- Wal-Mart (1)

- Walter Reed Army Medical Center (1)

- war (2)

- war crimes (16)

- war czar (3)

- war in Afghanistan (24)

- war in Iran (19)

- war in Iraq (300)

- war in Vietnam (2)

- war on terror (51)

- war reparations (1)

- warrantless wiretaps (23)

- Warren Buffett (2)

- Washington (1)

- water (12)

- Watergate (1)

- Wayne LaPierre (1)

- wealth disparity (1)

- weapons (2)

- Wendy Cortez (1)

- Western Oilsands (1)

- Westinghouse (1)

- What The Hell Are They Thinking? (1)

- What's the matter with (4)

- Where are the Democrats? (3)

- whistleblowers (2)

- White House Office of Administration (1)

- White House Press Briefing (4)

- Who Broke America? (1)

- Why they hate us (11)

- William Arkin (1)

- William E. Colby (1)

- William J. Haynes (1)

- William Koch (1)

- William Kristol (2)

- William P. Weidner (1)

- William Pryor Jr. (1)

- Wisconsin (2)

- WMD (6)

- Wolf Blitzer (1)

- Wolfeboro (1)

- women (12)

- World Bank (3)

- worthless media (7)

- wounded veterans (2)

- WTO (1)

- Wyoming (1)

- Xe (2)

- Your tax dollars (2)

- YouTube (1)

- Zarqawi (2)

- Zogby (1)

- Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (1)

Labels

- 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (1)

- 110th Congress (1)

- 1949 Geneva Conventions (4)

- 1949 Geneva Conventions-Fourth (1)

- 1949 Geneva Conventions-Third (1)

- 501 (c) (4) (1)

- 60 Minutes (1)

- 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (1)

- 9/11/01 (34)

- 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (2)

- Aaron Mate (1)

- Abd al-Rahim al-Nahsiri (1)

- Abdul-Mahdi (1)

- abortion (10)

- Abu Dhabi (1)

- Abu Ghraib (19)

- Abu Zubaydah (2)

- ACLU (3)

- activism (3)

- acts of misdirection? (3)

- Admiral Michael Mullen (1)

- advisory Board (1)

- Afghan civilians (1)

- Afghanistan (10)

- Ahmed Chalabi (1)

- Al Gore (4)

- Al Kamen (1)

- Al Qaeda (16)

- Al Sharpton (4)

- al-Hashemi (2)

- al-Mahdi (1)

- al-Maliki (11)

- al-Sistani (1)

- Alabama (3)

- Alan Greenspan (1)

- Alan Mollohan (1)

- Alan Simpson (1)

- Alaska (10)

- Alberto Gonzales (26)

- Alberto Mora (1)

- Alfa Group (1)

- Alphonse D'Amato (1)

- alternative media (1)

- amendment 2073 (1)

- American culture (49)

- American Petroleum Institute (1)

- Amy Goodman (7)

- An Inconvenient Truth (1)

- Analysis Corp (1)

- Anbar (3)

- Andrea Mitchell (1)

- Andrew Card (5)

- animals (15)

- Another Bush cock-up (4)

- Anthony Cordesman (1)

- Anthony Kennedy (1)

- Anthony Zinni (1)

- anthrax (6)

- antiquities (1)

- Antonia Juhasz (2)

- AQI (1)

- Arent Fox Kintner Plotkin and Kahn (1)

- Ari Fleischer (1)

- Arizona (3)

- Arkansas (1)

- Arlen Specter (14)

- arms sales (3)

- Armstrong Williams (3)

- Arnold Schwarzenegger (1)

- art (3)

- asbestos (2)

- Atlanta (1)

- audio (2)

- AUMF 2002 (1)

- Australia (1)

- Bab al-Sheik (1)

- Baghdad (1)

- Bagram (1)

- bailout (4)

- Bakhtawar Zardari (1)

- Bangladesh (1)

- Baqouba (1)

- Barack Obama (43)

- Barbara Bush (5)

- Barry Jackson (1)

- Basra (2)

- BCCI (2)

- Bearing Point (1)

- bees (2)

- Ben Bernanke (1)

- Ben Nelson (2)

- Benazir Bhutto (7)

- benchmarks (3)

- Benita Fitzgerald Mosley (2)

- Benjamin Netanyahu (1)

- Big Agra (7)

- Big Business (2)

- Big Oil (12)

- Big Pharma (1)

- BigAgra (1)

- Bilawal Bhutto (2)

- Bill Clinton (19)

- Bill Clinton was no friend to liberals (1)

- Bill Gates (1)

- Bill Keller (1)

- Bill Kristol (2)

- Bill Maher (1)

- Bill Moyers (2)

- Bill Richardson (3)

- Bill Sammon (2)

- birds (1)

- Blackstone (2)

- Blackwater (11)

- blogging (4)

- Bob Baer (2)

- Bob Corker (1)

- Bob Graham (1)

- Bob Perry (1)

- Bob Shrum (1)

- Bobby Jindal (2)

- Bolivia (1)

- books (30)

- boys will be boys (1)

- BP (4)

- BP America (1)

- BP PLC (1)

- Brad Delong (1)

- Bradley Schlozman (1)

- Brazil (1)

- Bremer's 100 Orders (2)

- Brent Scowcroft (3)

- Brewster Jennings (1)

- Brian Schweitzer (1)

- Brigadier General Janis Karpinski (3)

- Bruce Bartlett (1)

- Bruce Fein (1)

- Bruce McMahan (2)

- Bud Cummins (1)

- Bulgaria (1)

- Bureau of Diplomatic Security (1)

- Burma (3)

- Bush (89)

- Bush 1 administration (2)

- Bush administration (98)

- Bush family (2)

- Bush veto (4)

- Bush-speak (1)

- Bush's legacy (5)

- Bush's surge (38)

- CAFTA (1)

- California (20)

- Cambodia (1)

- Camp Bucca (2)

- Camp Cropper (1)

- campaign contributors (1)

- Canada (1)

- cancer (1)

- candidates' positions (1)

- capitalism (3)

- Carl Levin (4)

- Carl Lindner (1)

- Carlyle Group (3)

- Carol Lam (1)

- Caroline Cheeks Kilpatrick (1)

- CBO (1)

- CBS (3)

- celebrity gossip (2)

- censorship (3)

- Centers for Disease Control (1)

- Chad (1)

- Chalmers Johnson (1)

- Charles Duelfer (2)

- Charles Grassley (6)

- Charles Koch (2)

- Charlie Rangel (1)

- charts (1)

- Chechnya (1)

- chemical industry (1)

- Chevron (3)

- ChevronTexaco (1)

- Chicago (2)

- children (1)

- China (12)

- Chip Reid (1)

- Chris Dodd (4)

- Chris Hedges (1)

- Chris Matthews (10)

- Chris Van Hollen (2)

- Christian Coalition (1)

- Christine Todd Whitman (3)

- Christopher Hitchens (1)

- Chuck Schumer (9)

- CIA (36)

- CIA leak investigation (4)

- CIA tapes (1)

- Cindy Sheehan (3)

- Citibank (1)

- civil liberties (4)

- civil rights (5)

- Claire McCaskill (1)

- Clarence Page (2)

- Clarence Thomas (1)

- Cleveland (1)

- climate change (8)

- Clinton administration (2)

- cluster bombs (3)

- CNN (1)

- coal (2)

- Coalition Provisional Authority (4)

- Cofer Black (2)

- Cold War (2)

- Colin Powell (5)

- Colleen Rowley (3)

- Colombia (1)

- Colonel Thomas M. Pappas (3)

- Colorado (3)

- Condoleeza Rice (5)

- Congo (1)

- Congressional Record (1)

- Connecticut (1)

- Conoco (1)

- ConocoPhillips (1)

- Conservatives (5)

- conspicuous consumption (12)

- Contempt of Congress (2)

- contractors (17)

- corn (5)

- corporate welfare (1)

- corruption (27)

- Council for National Policy (4)

- Council on Foreign Relations (1)

- CPA (9)

- Craig Crawford (2)

- Craig Fuller (1)

- Craig Thomas (1)

- crumbling infrastructure (1)

- Cuba (11)

- culture (22)

- Curveball (1)

- Cynthia Tucker (1)

- Cyril Wecht (1)

- Czech Republic (1)

- D and E/D and X/Partial Birth Abortion (2)

- D.C. voting rights (1)

- Dan Abrams (1)

- Dan Bartlett (2)

- Dan Burton (1)

- Dan Metcalfe (1)

- Dan Rather (1)

- Daniel Ellsberg (2)

- Daniel Inouye (1)

- Darrell Issa (2)

- David Addington (1)

- David Albright (2)

- David Broder (1)

- David Brooks (1)

- David Frum (1)

- David Gergen (2)

- David Gregory (8)

- David Gribben (1)

- David Horgan (1)

- David Kay (1)

- David Koch (2)

- David M. McIntosh (1)

- David MacMichael (2)

- David Rivkin (1)

- David Shuster (1)

- David Vitter (6)

- death penalty (2)

- death toll (1)

- debates (5)

- Debra Wong Yang (1)

- Defense Appropriations Subcommittee (1)

- Defense Authoriation Act of 2006 (1)

- Defense Policy Board (1)

- Deforest Soaries (3)

- Democracy Now (11)

- Democratic Party (4)

- Democratic Presidential debates (2)

- Democrats (9)

- Democrats suck too (39)

- Denmark (2)

- Dennis Kucinich (3)

- Department of Homeland Security (3)

- deregulation (17)

- derivatives (1)

- Det Norske Oljeselskap (1)

- detainees (2)

- Detroit (2)

- Diane Beaver (1)

- Dianne Feinstein (7)

- Dick Cheney (37)

- Dick Cheney's energy task force (4)

- Dick Durbin (4)

- Dick Lugar (2)

- dirty tricks (17)

- dissent (1)

- Diyala (1)

- DLC politics (1)

- DNO (2)

- documents (1)

- DoD (1)

- dogs (2)

- DOJ (5)

- domestic spying (1)

- Don Evans (4)

- Don Imus (6)

- Don Siegelman (1)

- Donald Rumsfeld (12)

- Douglas Brinkley (1)

- Douglas Feith (4)

- Dr. Justin Frank (1)

- draft (2)

- Drew Westen (1)

- drought (2)

- drug bill (1)

- drugs-illicit (4)

- drugs-pharmaceutical (1)

- Duncan Hunter (1)

- E.J. Dionne (1)

- earmarks (4)

- Ebay (1)

- economics (23)

- economy (81)

- Ecuador (1)

- Ed Markey (1)

- Ed Rogers (1)

- education (5)

- Egypt (2)

- Ehud Olmert (1)

- El Salvador (2)

- election 1980 (1)

- election 1992 (1)

- election 2000 (8)

- election 2002 (1)

- election 2008 (45)

- election reform (4)

- elections 2002 (2)

- elections 2004 (1)

- elections 2006 (4)

- elections 2008 (76)

- elections 2012 (1)

- electionws 2004 (1)

- Elian Gonzalez (1)

- Elijah Cummings (1)

- Elizabeth Dole (1)

- Ellen Tauscher (1)

- Elliot Abrams (1)

- email (4)

- ENDGAME (1)

- endorsements (3)

- energy (13)

- energy nuclear (2)

- energy nuclear (1)

- energy policy (6)

- entertainment (7)

- environment (59)

- environmental (1)

- EPA (3)

- Eric Edelman (1)

- Eric Holder (1)

- Eric Prince (2)

- Estonia (1)

- ethanol (1)

- ethics (2)

- Eugene Robinson (2)

- European Union (1)

- executive order 12334 (1)

- executive order 12472 (1)

- executive order 12656 (1)

- executive order 12958 (1)

- executive order 13228 (1)

- executive order 13233 (2)

- executive order 13303 (1)

- executive order 13315 (1)

- executive order 13350 (1)

- executive orders (8)

- Executive Privilege (4)

- Exxon (1)

- ExxonMobil (5)

- Fairness Doctrine (1)

- faith-based organizations (2)

- Fallujah (2)

- Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (1)

- Farm Bill (5)

- Faye Williams (1)

- FBI (16)

- FCC (2)

- FDA (6)

- FDIC (1)

- FEC (1)

- Federal Reserve (4)

- Federalist Society (1)

- FEMA (1)

- filibuster (1)

- financial disclosure (1)

- first amendment (11)

- FISA bill (13)

- fish (3)

- flat tax (1)

- FOIA (1)

- food (46)

- For the children (2)

- For the common good (2)

- Foreign Intelligence cronyism (1)

- fourth amendment (1)

- Fox News (1)

- France (2)

- Frances Townsend (2)

- Frank Murkowski (1)

- Frank Rich (1)

- Frank Riggs (1)

- Fred Fielding (2)

- Fred Koch (1)

- Fred Thompson (15)

- free speech (3)

- free trade (1)

- freedom and democracy in Iraq (6)

- Freedom of Information Act of 2007 (1)

- Freedom to dissent...NOT (1)

- Freedom's Watch (2)

- Frontline (1)

- FUBAR (7)

- Futile Care Law (1)

- Gail Norton (2)

- GAO (7)

- gay rights (3)

- Gaza (2)

- Gazprom (1)

- gender inequality (4)

- Genel Enerji (1)

- General David Petraeus (6)

- General Electric (1)

- General Eric Shenseki (1)

- General Michael Hayden (6)

- General Tommy Franks (1)

- George H.W. Bush (10)

- George Lakoff (1)

- George P. Bush (1)

- George Tenet (15)

- George Voinovich (1)

- Georgia (7)

- Georgia Maryland (1)

- Georgia Pacific Corp. (1)

- Georgia Thompson (1)

- Germany (4)

- Getting To Know Your Adversary (1)

- Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 (1)

- Glenn Greenwald (1)

- global warming (20)

- globalization (2)

- GMO (2)

- Gonzales vs. Carhart (1)

- GOP (12)

- Gordon Brown (2)

- Governor Jim Doyle (1)

- Great Britain (22)

- Greg Thielmann (1)

- Grover Norquist (3)

- Guantanamo (20)

- Guatemala (1)

- Gulf of Mexico (2)

- Gulf War 1 (3)

- guns (2)

- H.R. 1255 (1)

- H.R. 1591 (1)

- H.R. 2206 (1)

- H.R. 3222 (1)

- H.R. 4156 (1)

- H.R. 4241 (1)

- Hague Regulations of 1907 (3)

- Haiti (1)

- Haley Barbour (1)

- Halliburton (6)

- Hamid Karzai (1)

- Hardball (16)

- Harold Ford Jr. (1)

- Harold Ickes (1)

- Harold Simmons (1)

- Harriet Miers (4)

- Harry Reid (9)

- Hatch Act (1)

- Hawaii (1)

- health (65)

- health care reform (1)

- health insurance (6)

- hearings (1)

- hedge fund managers (2)

- hedge funds (2)

- Helms-Burton Act (1)

- Henry Kissinger (1)

- Henry Paulson (3)

- Henry Waxman (8)

- Hezbollah (1)

- Hillary Clinton (62)

- holidays (2)

- homeland security (2)

- Homeland Security appropriations bill (1)

- House Appropriations Committee (3)

- House Committee on Intelligence (3)

- House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform (6)

- House Foreign Affairs Committee (1)

- House Judiciary Committee (5)

- House Natural Resources Committee (1)

- House Republicans (6)

- housing (1)

- Howard Fineman (3)

- Howard Wolfson (1)

- HR 1955 (1)

- HSPD 20 (2)

- Huffington Post (1)

- Hugo Chavez (2)

- human rights (13)

- Hungary (1)

- Hurricane Katrina (2)

- Hypocrisy 101 (4)

- Idaho (1)

- Ideas Whose Time Has Come? (1)

- illegal immigration (7)

- Illinois (3)

- IMF (4)

- impeachment (12)

- implosions (10)

- In our names (19)

- India (1)

- Indiana (4)

- Indonesia (1)

- insurgency (1)

- intelligence (9)

- Internet (7)

- interviews (19)

- Invocon (1)

- Iowa (3)

- IPO (1)

- Iran (27)

- Iran-Contra (1)

- Iran-Iraq war (1)

- Iraq (42)

- Iraq czar (1)

- Iraq elections (2)

- Iraq Health Ministry (1)

- Iraq occupation (2)

- Iraq Petroleum Company (1)

- Iraq reconstruction (5)

- Iraq Study Group (1)

- Iraq Survey Group (2)

- Iraqi army (1)

- Iraqi civilians (13)

- Iraqi Islamic Party (1)

- Ireland (1)

- Ishaqi (1)

- Islam (1)

- Israel (18)

- Issam Al-Chalabi (1)

- Italy (1)

- Iyad Allawi (1)

- Jack Abramoff (1)

- Jack Reed (2)

- James Baker (2)

- James Carville (3)

- James Comey (6)

- James Dobson (1)

- James Inholfe (1)

- James K. Haveman (1)

- James Schlesinger (1)

- James Sensenbrenner (1)

- James Woolsey (3)

- James Yousef Yee (1)

- Jan Schakowsky (1)

- Jane Dalton (1)

- Jane Harman (3)

- Japan (2)

- Jay Dardenne (1)

- Jay Leno (1)

- Jay Rockefeller (6)

- Jean Shaheen (4)

- Jean-Baptiste Aristide (1)

- Jean-Bertrand Aristide (1)

- Jeff Sessions (3)

- Jeffrey Toobin (1)

- Jennifer Fitzgerald (1)

- Jeremy Scahill (3)

- Jerrold Nadler (2)

- Jerry Lewis (1)

- Jesse Helms (1)

- Jesse Jackson (1)

- Jill Abramson (1)

- Jim Bunning (1)

- Jim DeMint (2)

- Jim Donelon (1)

- Jim Gilmore (1)

- Jim Hightower (2)

- Jim Marcinkowski (1)

- Jim McCrery (1)

- Jim McGovern (1)

- Jim Miklaszewski (1)

- Jim Moran (1)

- Jim O'Beirne (2)

- Jim Rogers (3)

- Jim VandeHei (1)

- Jim Webb (2)

- Jimmy Breslin (1)

- Jimmy Carter (1)

- Jo Ann Emerson (1)

- Joan Baez (1)

- Joe Allbaugh (1)

- Joe Biden (4)

- Joe Conason (3)

- Joe DiGenova (2)

- Joe Klein (1)

- Joe Lieberman (5)

- Joe Scarborough (1)

- Joe Wilson (9)

- John Ashcroft (7)

- John B. Taylor (1)

- John Barrasso (1)

- John Boehner (3)

- John Bolton (1)

- John Conyers (5)

- John Cornyn (1)

- John D. Bates (1)

- John Danforth (1)

- John Dean (2)

- John Dingell (2)

- John Edwards (9)

- John Gilmore (2)

- John Harris (2)

- John Harwood (2)

- John Kerry (3)

- John King (1)

- John McCain (11)

- John Mellencamp (1)

- John Murtha (3)

- John Nichols (2)

- John Roberts (4)

- John Sununu (3)

- John Warner (4)

- John Yoo (1)

- John Zogby (1)

- Joint Chiefs of Staff (2)

- Jon Corzine (1)

- Jonathan Alter (2)

- Jonathan Cohn (1)

- Jonathan Turley (1)

- Jordan (4)

- Jose Padilla (1)

- Joseph Stiglitz (1)

- Josh Bolten (2)

- Judith Miller (2)

- Judith Nathan Giuliani (1)

- K Street (2)

- Kamil Mubdir Gailani (1)

- Karbala (1)

- Karen Hughes (1)

- Karl Rove (25)

- Kate O'Beirne (2)

- Kazakhstan (1)

- Keith Olbermann (6)

- Ken Blackwell (1)

- Ken Mehlman (1)

- Ken Pollack (1)

- Ken Salazar (1)

- Ken Starr (1)

- Ken Wainstein (1)

- Kennedy family (1)

- Kenneth Blackwell (1)

- Kentucky (1)

- Ketchum (1)

- Khalid Sheik Mohammed (1)

- King Abdullah (1)

- Kit Bond (2)

- Kitty Kelley (1)

- knuckle-dragging Americans (1)

- Koch brothers (2)

- Koch Industries (1)

- KRG (1)

- Kristin Breitweiser (1)

- Kurdistan (3)

- Kurdistan Regional Government (2)

- Kurds (7)

- Kyle Sampson (1)

- L-1 Identity Solutions (1)

- Lamar Alexander (2)

- Lancet study (9)

- Lanny Griffith (1)

- Larry Craig (2)

- Larry Ellison (1)

- Larry Johnson (2)

- Larry Lindsey (1)

- Larry Summers (1)

- Larry Wilkerson (1)

- Las Vegas (3)

- Latvia (1)

- Laura Bush (1)

- Laurie David (1)

- Lawrence Korb (1)

- Leandro Aragoncillo (1)

- Lebanon (3)

- Lee Hamilton (1)

- legislation (30)

- Leon Panetta (1)

- Liberals (2)

- Libya (4)

- Lieutenant General Ricardo S. Sanchez (1)

- Lindsay Graham (6)

- Lisa Murkowski (1)

- lobbyists (6)

- Lockerbie (3)

- Lois Romano (1)

- London (1)

- long war (1)

- Loretta Sanchez (1)

- Lou Dubose (1)

- Louisiana (7)

- Lt. Colonel Steven Jordan (2)

- Lt. General Douglas Lute (2)

- Lt. General Martin Dempsey (1)

- Lt. General Ricardo Sanchez (1)

- Lukoil (1)

- Lynndie England (1)

- Madrid bombings (1)

- Mahdi Army (1)

- Mahmoom Khaghani (1)

- Maine (3)

- mainstream media (8)

- Major General Antonio Taguba (1)

- Major General Benjamin R. Mixon (1)

- Major General Geoffrey Miller (11)

- maps (1)

- Margaret Carlson (1)

- Marion Spike Bowman (2)

- Mark Corallo (1)

- Mark McKinnon (1)

- Mark Mix (1)

- Mark Penn (2)

- Mark Pryor (1)

- martial law (1)

- Mary Beth Buchanan (3)

- Mary Cheney (1)

- Mary Landrieu (1)

- Mary Matalin (2)

- Maryland (2)

- Massachusetts (2)

- Matt Brooks (1)

- Matt Cooper (1)

- Matthew Mead (1)

- Maury Wills (1)

- Max Baucus (1)

- media (15)

- Medicaid (1)

- medical ethics (1)

- Meet the Press (4)

- Meghan O'Sullivan (1)

- Mel Sembler (1)

- meltdown (16)

- men (1)

- mental health (11)

- mental illness (6)

- Mexico (4)

- Michael Allan Leach (1)

- Michael Bloomberg (1)

- Michael Chertoff (6)

- Michael Eric Dyson (1)

- Michael Garcia (1)

- Michael Ledeen (1)

- Michael Moore (4)

- Michael Mukasey (13)

- Michael O'Hanlon (2)

- Michael Pollan (7)

- Michael R. Gordon (2)

- Michael Scheuer (2)

- Michael Steele (1)

- Michael Turk (1)

- Michelle Obama (1)

- Michigan (2)

- Mickey Herskowitz (1)

- Middle East (15)

- Mike Barnicle (1)

- Mike Huckabee (9)

- Mike McConnell (3)

- Mike Mullen (1)

- military budget (5)

- Military Commissions Act of 2006 (1)

- military equipment (15)

- Military Industrial Complex (4)

- military tribunals (1)

- Milwaukee (1)

- Minnesota (2)

- Mississippi (2)

- Missouri (1)

- Mitch McConnell (4)

- Mitt Romney (9)

- Molly Ivins (2)

- moments in history (1)

- Monica Goodling (1)

- Monica Lewinsky (1)

- Montana (3)

- Most Ethical Congress (1)

- MoveOn.org (2)

- movies (2)

- MSNBC (3)

- multinational corporations (2)

- Murray Waas (2)

- N. Korea (4)

- NAFTA (3)

- Najaf (1)

- Nancy Pelosi (16)

- Naomi Klein (10)

- Naomi Wolf (1)

- narcissistic personality disorder (1)

- Nat Parry (1)

- National Defense Authorization Act for 2008 (4)

- National Guard (2)

- National Republican Congressional Committee (1)

- National Security (1)

- National Security Archive (2)

- National Security Decision Directive 188 (1)

- Neil Bush (2)

- Nelson Cohen (3)

- Neoconservatives (4)

- Netherlands (1)

- Nevada (1)

- New Afghanistan (3)

- New Hampshire (8)

- New Iraq (51)

- New Jersey (1)

- New Orleans (1)

- New World Order (9)

- New York (7)

- New York Times (5)

- New Yorker (1)

- Newsweek (8)

- Newt Gingrich (2)

- NIE (4)

- NIH (1)

- Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (2)

- No Child Left Behind (1)

- No WMD (2)

- Noam Chomsky (1)

- Norm Coleman (1)

- North Carolina (3)

- Now That Obama's President - What's Left To Do? (1)

- NRC (1)

- NRCC (1)

- NSA (6)

- NSL (2)

- NSPD 51 (2)

- nuclear (12)

- Obama administration (10)

- obituaries (2)

- oceans (4)

- offshoring (1)

- Ohio (3)

- oil (14)

- oil and gas (20)

- oil law (21)

- Oklahoma (1)

- Oliver North (1)

- Olympia Snowe (1)

- OPEC (3)

- Operation Clean Break (1)

- Operation Rescue (1)

- Oprah Winfrey (1)

- Order 37 (2)

- Order 39 (3)

- Order 40 (1)

- Oregon (1)

- organic farming (1)

- organized labor (7)

- Orrin Hatch (1)

- Osama Bin Laden (9)

- outsourcing (1)

- owls (1)

- PACS (1)

- Pakistan (15)

- Pakistan's People's Party (2)

- Palestinians (2)

- Pan Am 103 (2)

- Paris Hilton (2)

- parliamentary procedure (1)

- passportgate (2)

- Pat Buchanan (4)

- Pat Leahy (2)

- Pat Roberts (4)

- Pat Tillman (2)

- Patrick Lang (1)

- Patrick Leahy (10)

- Patrick McHenry (1)

- Patriot Act (12)

- Patty Murray (1)

- Paul Allen (1)

- Paul Bremer (9)

- Paul Craig Roberts (1)

- Paul Eaton (1)

- Paul Krugman (8)

- Paul O'Neill (1)

- Paul Rieckhoff (2)

- Paul Wellstone (1)

- Paul Weyrich (1)

- Paul Wolfowitz (5)

- PDVSA (1)

- Peak oil (2)

- Pennsylvania (4)

- Pentagon (22)

- people (1)

- Pervez Musharraf (10)

- Pete Domenici (1)

- Peter King (1)

- Petoil (1)

- Petrel Resources (1)

- Phil Gingrey (1)

- Phil Giraldi (1)

- Phil Griffin (1)

- Philip Atkinson (1)

- Philip Zelikow (1)

- Phillipines (2)

- photos (66)

- Phyllis Schlafly (1)

- PKK (1)

- Plan B (1)

- PNAC (1)

- Poland (1)

- police brutality (2)

- political fundraising (1)

- political operatives (1)

- polls (4)

- population control (1)

- Porter Goss (2)

- poverty in America (3)

- Presidential candidates (8)

- Presidential Directives (1)

- Presidential pardons (1)

- Presidential Records Act of 1978 (6)

- press releases (1)

- prewar intelligence (1)

- Prince Bandar bin Sultan (2)

- prisons (6)

- privacy (15)

- Privacy Act of 1974 (1)

- private contractors (1)

- private equity (2)

- privatization (20)

- Profiles (11)

- Project Checkmate (1)

- propaganda (4)

- Protect America Act (2)

- PSA (1)

- psychologists (1)

- Psychology Today (1)

- PTSD (1)

- public relations (1)

- Puerto Rico (2)

- Pulitizer prizes (1)

- Putin (3)

- QinetiQ (1)

- Quds (1)

- race card (7)

- Rachel Maddow (3)

- racism (4)

- Rahm Emanuel (1)

- Ramadi (1)

- Ramzi Yousef (1)

- Rand Corporation (2)

- Ray McGovern (6)

- Reagan administration (1)

- real estate (2)

- Reasons not to vote for Republicans (22)

- Reasons we need campaign finance reform (7)

- recess appointment (1)

- red flags (1)

- reference file (1)

- reference papers (1)

- refugees (3)

- religion (3)

- rendition (2)

- reports (1)

- Republican Party (3)

- Republicans (15)

- Richard Armitage (1)

- Richard Baker (1)

- Richard Clarke (1)

- Richard E. Stickler (1)

- Richard Mellon Scaife (2)

- Richard Nixon (2)

- Richard Perle (6)

- Richard Viguerie (1)

- Richard Wolffe (1)

- Rick Santorum (1)

- right-wing organizations (2)

- RNC (7)

- Robert Dreyfuss (1)

- Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (2)

- Robert Fisk (1)

- Robert Gates (9)

- Robert Johnson (1)

- Robert Kuttner (1)

- Robert Mueller (10)

- Robert Novak (3)

- Robert Parry (6)

- Robert Reich (1)

- Rodney Alexander (1)

- Roger Simon (2)

- Roger Stone (2)

- Romania (1)

- Ron Brownstein (2)

- Ron Paul (3)

- Ron Reagan (1)

- Ron Suskind (1)

- Ron Wyden (1)

- Ronald Reagan (3)

- Roslynn Mauskopf (1)

- Royal Dutch Shell (3)

- Royal Dutch/Shell Group of Cos. (1)

- Rudy Giuliani (5)

- Rudy Guiliani (1)

- rule of law (8)

- Rush Holt (1)

- Russ Feingold (2)

- Russell Feingold (1)

- Russell Simmons (1)

- Russia (4)

- Rwanda (1)

- Ryan Crocker (3)

- S. 1927 (4)

- S. 1932 (1)

- S. 2340 (1)

- S. Carolina (4)

- S. Dakota (1)

- S. Korea (1)

- Sabrina D. Harman (1)

- Saddam Hussein (3)

- Sadr City (1)

- SAIC (1)

- Sam Bodman (1)

- Sam Brownback (2)

- Samarra (2)

- San Francisco (4)

- sanctions (1)

- Sandra Day O'Connor (2)

- Sara Taylor (4)

- Sarah Palin (7)

- Sarkozy (1)

- Saudi Arabia (17)

- Savings and Loan crisis (3)

- science (2)

- Scooter Libby (8)

- Scott Ritter (2)

- SEC (1)

- secrecy (12)

- secret government (2)

- secret holds (1)

- secret prisons (4)

- Secret Service (3)

- secular democracy (1)

- Senate Appropriations subcommittee (2)

- Senate Armed Services Committee (3)

- Senate Energy and Commerce Committee (1)

- Senate Ethics Committee (1)

- Senate Finance Committee (2)

- Senate Intelligence Committee (6)

- Senate Judiciary Committee (22)

- Senate Republicans (1)

- senior issues (2)

- Separation of church and state (8)

- Sergeant Michael J. Smith (1)

- Sergeant Santos A. Cardona (1)

- sex (1)

- sex crimes (1)

- Seymour Hersh (7)

- Sheldon Adelson (2)

- Shell Oil (6)

- Sheryl Crow (1)

- Shiite militias (1)

- shrines (2)

- Sibel Edmonds (1)

- Sibiyha Prince (1)

- Sidney Blumenthal (2)

- SIGIR (1)

- signing statements (1)

- Slovakia (1)

- slow food (2)

- socialism (1)

- SOFA (1)

- Spain (2)

- Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction (1)

- special ops (1)

- Specialist Charles Graner (1)

- speeches (2)

- Stephen Cambone (1)

- Stephen Hadley (8)

- Steve Capus (2)

- Steve Fraser (1)

- Steve McMahon (2)

- Steve Scalise (1)

- Steven Biskupic (1)

- Stuart Bowen (1)

- summer reading list (1)

- Sunni (2)

- sunshine laws (1)

- superdelegates (2)

- supplemental appropriations bill (9)

- Susan Collins (2)

- Susan Page (1)

- Susan Ralston (1)

- Swift Boat veterans (1)

- Swift Boat Veterans for Truth (1)

- Syria (13)

- T. Boone Pickens (1)

- Taguba report (2)

- Talabani (2)

- Taliban (2)

- TALON (1)

- TANG (1)

- taxes (1)

- Ted Kennedy (1)

- Ted Olson (1)