McClatchy reports:

This year Senate Republicans are threatening filibusters to block more legislation than ever before, a pattern that's rooted in — and could increase — the pettiness and dysfunction in Congress.

The trend has been evolving for 30 years. The reasons behind it are too complex to pin on one party. But it has been especially pronounced since the Democrats' razor-thin win in last year's election, giving them effectively a 51-49 Senate majority, and the Republicans' exile to the minority.

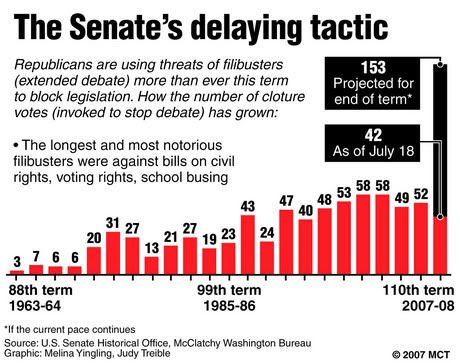

Seven months into the current two-year term, the Senate has held 42 "cloture" votes aimed at shutting off extended debate — filibusters, or sometimes only the threat of one — and moving to up-or-down votes on contested legislation. Under Senate rules that protect a minority's right to debate, these votes require a 60-vote supermajority in the 100-member Senate.

Democrats have trouble mustering 60 votes; they've fallen short 22 times so far this year. That's largely why they haven't been able to deliver on their campaign promises.

By sinking a cloture vote this week, Republicans successfully blocked a Democratic bid to withdraw combat troops from Iraq by April, even though a 52-49 Senate majority voted to end debate.

This year Republicans also have blocked votes on immigration legislation, a no-confidence resolution for Attorney General Alberto Gonzales and major legislation dealing with energy, labor rights and prescription drugs.

Nearly 1 in 6 roll-call votes in the Senate this year have been cloture votes. If this pace of blocking legislation continues, this 110th Congress will be on track to roughly triple the previous record number of cloture votes — 58 each in the two Congresses from 1999-2002, according to the Senate Historical Office.

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., forced an all-night session on the Iraq war this week to draw attention to what Democrats called Republican obstruction.

"The minority party has decided we have to get to 60 votes on almost everything we vote on of substance," said Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo. "That's not the way this place is supposed to work."

Even Sen. Trent Lott, R-Miss., who's served in Congress since 1973, complained that "the Senate is spiraling into the ground to a degree that I have never seen before, and I've been here a long time. All modicum of courtesy is going out the window."

But many Republicans say the Senate's very design as a more deliberative body than the House of Representatives is meant to encourage supermajority deal-making. If Democrats worked harder to seek bipartisan deals, Republicans say, there wouldn't be so many cloture votes.

"You can't say that all we're going to do around here in the United States Senate is have us govern by 51 votes — otherwise we might as well be unicameral, because then we would have the Senate and the House exactly the same," said Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz.

To which Reid responds: "The problem we have is that we don't have many moderate Republicans. I don't know what we can do to create less cloture votes other than not file them, just walk away and say, 'We're not going to do anything.' That's the only alternative we have."

Some Republicans say that Reid forces cloture votes just so he complain that they're obstructing him.

Sen. Arlen Specter, R-Pa., called the all-nighter on Iraq "meaningless, insulting" and "an indignity." "There is no doubt that there are not 67 votes present to override a veto. There is little doubt that there are not 60 votes present to bring the issue to a vote."

Republicans also say that Democrats are forgetting how routinely they threatened filibusters only a few years ago when they were the minority, especially to block many of President Bush's judicial nominees. Back then, Republicans were so mad that they considered trying to change Senate rules to eliminate filibusters — but didn't.

"The suggestion that it's somehow unusual in the Senate to have controversial matters decided by 60 votes is absurd on its face," said Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.

Although this year's Congress is taking it to a new level, the frequency of cloture votes has been climbing for decades — the result of more polarized politics in Congress and also evolving Senate rules and practices.

Associate Senate Historian Don Ritchie said that since the nation's start, dissident senators have prolonged debate to try to kill or modify legislation. The word "filibuster" — a translation of the Dutch word for "free-booter" or pirate — appears in the record of an 1840s Senate dispute about a patronage job.

From Reconstruction to 1964, the filibuster was largely a tool used by segregationists to fight civil rights legislation. Even so, filibusters were employed only rarely; there were only three during the 88th Congress, which passed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 after two months of filibustering.

Filibusters were infrequent partly because the Senate custom of civility prompted consideration of minority views — and partly because they were so hard to overcome that compromises were struck. In 1917 cloture rules for ending filibusters were put in place, but required a two-thirds vote — so high it was rarely tested.

Post-Watergate, in 1975, the bar was lowered to three-fifths, or 60 votes, and leaders began to try it more often.

By the early 1990s, tensions between then-Majority Leader George Mitchell of Maine and Minority Leader Bob Dole of Kansas upped the ante, and the filibuster-cloture spiral has soared ever since as more partisan politics prevailed. The use of filibusters became "basically a tool of the minority party," Ritchie said.

The current Senate has two other complications: the 51-49 Democratic majority, which includes a pro-war independent and an absent Democrat recuperating from brain surgery, makes it harder to find 60 votes. And the presidency and Congress are controlled by opposing parties, which increases confrontation.

The Senate "has always been a cumbersome and frustrating and slow body because that's what the Constitution wanted," Ritchie said. The new majority's decisions are: "How often are you willing to lose on these issues? Would you rather campaign on the other side being obstructionists? What's a tolerable compromise? They're still working these things out."

Republican Senate leader McConnell said Friday in a news conference that when he became minority leader, "it was not my goal to see us do nothing. I mean, you can always use the next election as a rationale for not doing anything. But as you all know, we've had a regularly scheduled election every two years since 1788, so there's always an election right around the corner."

"A divided government has frequently done important things: Social Security in the Reagan period, when (Democrat) Tip O'Neill was speaker; welfare reform when Bill Clinton was in the White House when there was a Republican Congress. There's no particular reason why divided government can't do important things. We haven't yet, but it's not too late.

"And I think clearly the way to accomplish things is in the political middle, and I would challenge our friends on the other side of the aisle to step up and take a chance on something big and important for our country."

Of course, Democrats say similar things — but then neither side often compromises.

Friday, July 20, 2007

Senate Tied In Knots By Filibusters

Posted by Maeven at 11:45 PM

Labels: charts, filibuster, Harry Reid, Mitch McConnell, U.S. Senate